The Promised Land is generally intended as the land of Israel, which, according to the Bible’s Old Testament, God promised and subsequently gave to Abraham and several more times to his descendants. Metaphorically speaking, the idea of a Promised Land is also well suited for describing 3D printing’s potential, as the AM industry grows trying to deliver a better, more efficient and more sustainable way of producing all types of objects and parts. So it should not come as a surprise that many Israeli 3D printing companies are among the world leaders in the development of new AM technologies.

It started with Objet (now merged with Stratasys) but even before that, it was large-format digital 2D printing at Indigo and Scitex (now part of HP), laying the foundation for jetting-based 3D printing processes. This huge knowledge base has sprouted many new startups (and continues to do so). Some were founded shortly after the Stratasys-Objet merger: companies like XJet and Massivit are now starting to reap the fruits of nearly a decade of advanced development on unique technologies.

A new generation of Israeli 3D printing companies is entering the market now, bringing innovative solutions that will enable AM to break through into higher productivity segments. For example, we are talking about companies such as 3DM, Largix, and Tritone, among others, that are putting a truly original twist and turning the tables on consolidated AM processes such as polymer LFAM, metal and composites 3D printing or polymer laser PBF.

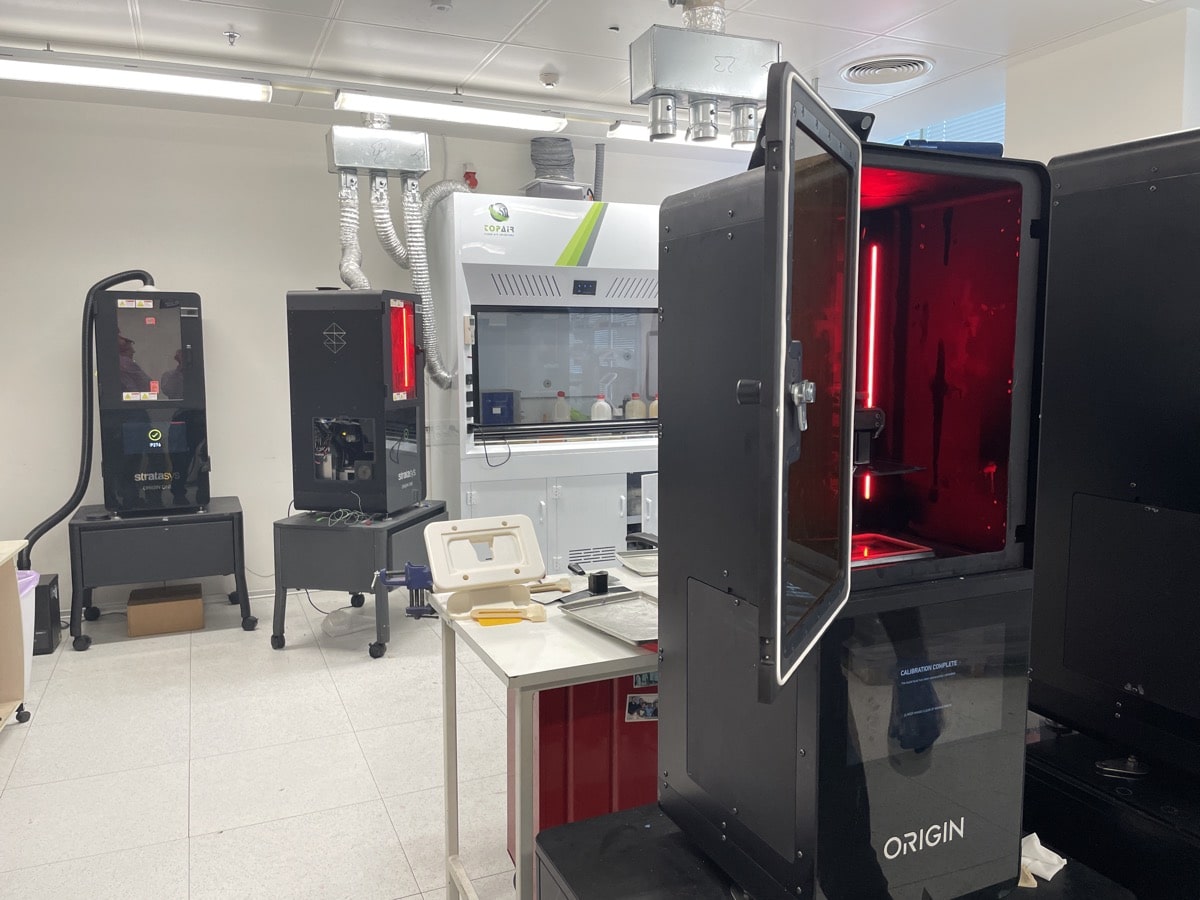

Stratasys, the global 3D printing market leader, stands over all other Israeli 3D printing companies, providing an example of resiliency and success, even against the many challenges that have characterized the AM industry’s growth. Beyond the two base technologies (FDM and Polyjet), Stratasys recently added new state-of-the-art thermal powder bed fusion (SAF), SLA and layerless high-speed DLP photopolymerization (Origin’s PPP process) to its increasingly advanced PolyJet (material jetting) and (mainly US-based) industrial filament extrusion technologies.

These are not the only Israeli 3D printing companies advancing the state of the art of AM across global markets: more exist and are continuously emerging but, even if it is a small, well-connected, country there is only so much time to visit them all. But we tried to so let’s go.

Consolidated market leadership

Stratasys is the global leader in the 3D printing market. While the company has struggled through challenging times in the past, it remains the market leader and is able to provide a constantly growing array of solutions, products, and applications through a wide range of technologies. The Israeli side of the company focuses on the resin business and the HQ in Rehovot is where all new R&D and new applications are developed for the established PolyJet business as well as the recently introduced SLA (Neo from RPS and Covestro/DSM materials) and high-speed DLP (Origin) businesses.

While hardware production takes place in a separate remote facility in Kiryat Gat, Polyjet technology and application do remain the main focus for the Rehovot HQ (which was voted among the architecturally best buildings in Israel). Polyjet has been around for two decades, but the feeling is that Stratasys has only begun to scratch the surface of its full potential. Compared to just a few years ago, there are many more systems on the market including those that are very much segments specific (for textiles, dental, medical) and those that are much more accessible (faster, smaller, more affordable) such as the new J55 and J35, with spinning tray technology.

Weaving the lines of AM

This translates into two businesses that Stratasys has identified as key for Polyjet’s mass adoption. The first is printing on textiles. What started as an explorative project (we covered its genesis when the dedicated 3D printer, the J850 Tech Style, was launched at Milan Design Week) is now becoming a major business opportunity and one where 3D printing’s value proposition is most evident. It’s not easy to effectively, accurately and precisely print complex patterns on textiles, and to make sure they stick, but the technology now seems to have reached a quality level sufficient to achieve full commercialization. If the fashion industry decides to massively adopt it, it would be a huge breakthrough. While there are competing color material jetting technologies on the market no one can come close to the level of Stratasys’ dedicated J850 Tech Style systems in this area.

Taking a bite out of the biggest cake

The other major segment that Stratasys is targeting with multiple products and numerous innovations is the dental industry. The legacy Eden systems have been among the most popular products for the dental industry but now many more competitors have entered the market even as the number of dental applications and adopters has continued to grow. Stratasys offers several systems for dental part manufacturing, all the way up to the giant J4100 for mass production and with a particular emphasis on the J5 DentaJet. This compact full-color system is the key element in the recently announced partnership with intraoral 3D scanner manufacturer 3shape for a 3MF-based digital workflow on full-color dental models. We are now fairly certain that this year’s IDS show in Cologne, Germany, will be a major milestone for Stratasys’ dental business as it will be for several other AM companies.

Future leaders growing up

Polyjet technology, such as that offered by Stratasys, is the most technologically advanced 3D printing technology on the market today and the only one that can offer voxel-level control of materials. At the same time, the materials initially used for PolyJet applications were too costly and not sufficiently durable for higher throughput production, making it ideally suited for advanced prototyping, modeling and tooling but not for final parts. That has changed now, with textile and other consumer product applications but, in the past, it was not always strategically important for Stratasys, to produce final, durable industrial final parts via Polyjet since it could do so via its FDM business using engineered thermoplastics. So new Israeli 3D printing companies emerged, founded by former Objet staff, that aimed to apply their material jetting knowledge in new ways or to new types of materials.

XJet

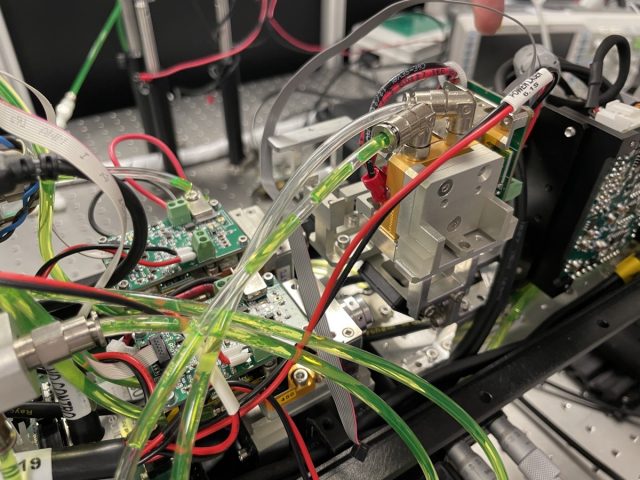

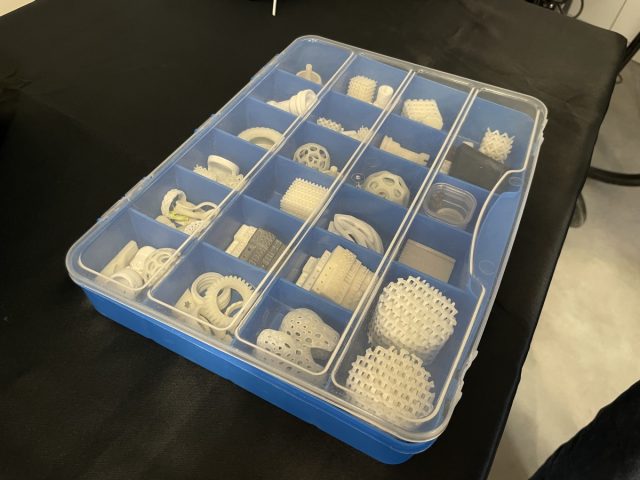

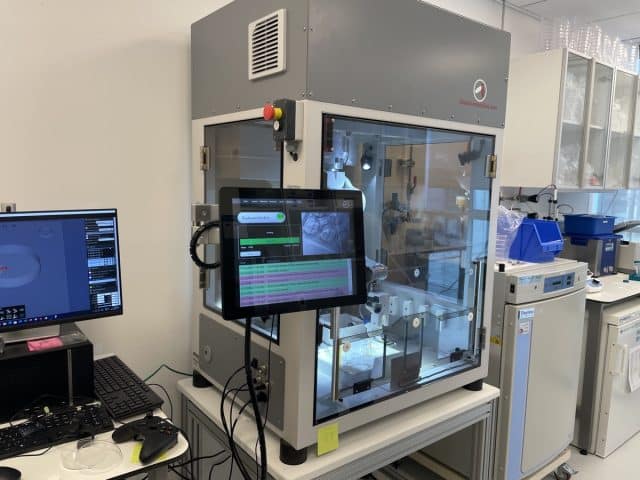

With nanoparticle jetting, XJet is the largest and best-funded among these “second gen” Israeli 3D printing companies. The company launched a new process that can jet ceramic and metal nanoparticles to produce dense green parts that can subsequently be easily sintered to obtain the final parts. The technology offers a printing speed that is comparable to metal binder jetting but the ability to jet a metal or ceramic nanoparticle water-based solution onto a platform (rather than jet binder onto a powder) offers several advantages. For example, not having to deal with messy fine powders (the XJet materials come in closed containers), to jet only the material needed (so that no powder recycling is necessary), and jet water-soluble materials along with the nanoparticles to obtain the same complex geometries that can be obtained via support-free metal binder jetting.

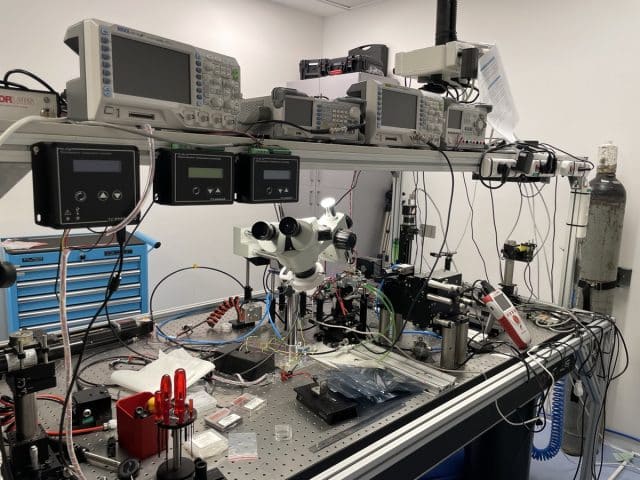

In addition, because the green parts are highly dense, they can be sintered at lower temperatures, for shorter times and much lower shrinkage, resulting in smooth surfaces and extremely high detail with thin walls. The downside to offering such and advanced and unique process is that fine-tuning the XJet Carmel systems in order to guarantee a high level of repeatability has taken a long time. The upside is that, according to Guy Zimmerman, XJet’s Chief Marketing Officer, that time has now arrived and it’s just in time to exploit the renewed industry focus on non-PBF metal AM technologies brought on by HP’s GE’s and Desktop Metal’s introduction metal binder jetting systems for high-throughput production.

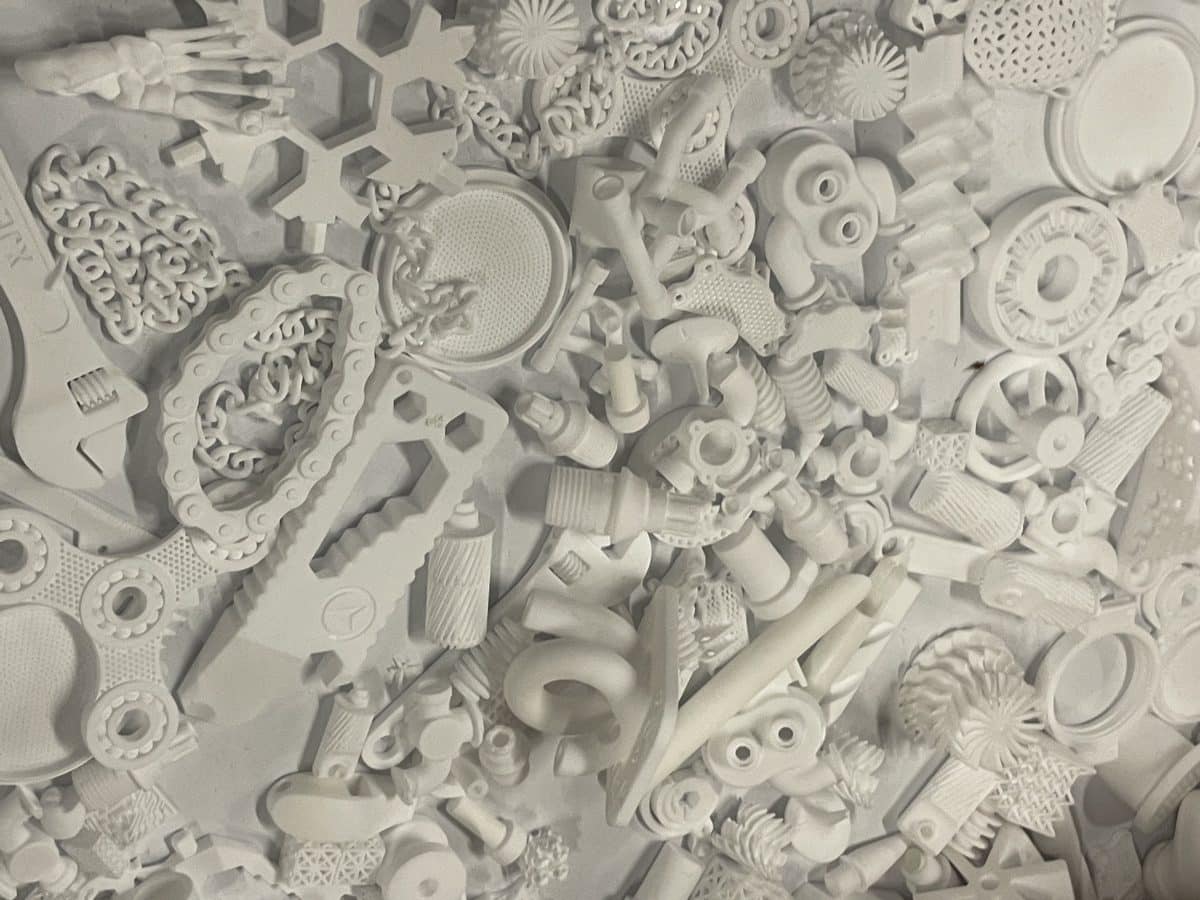

One thing that was clearly visible during our visit to XJet’s AMC (Additive Manufacturing Center) in Rehovot, compared to the last time we were here in 2019, was the higher number of 3D printers running. Even more importantly, we saw a much higher number of serially manufactured metal and ceramic parts laying around, especially considering that the company is not offering AM services but only developing applications for current or potential customers. While the number of available materials is limited to Zirconia and Steel, the quality, surface smoothness, and precision of these parts were impressive.

Massivit

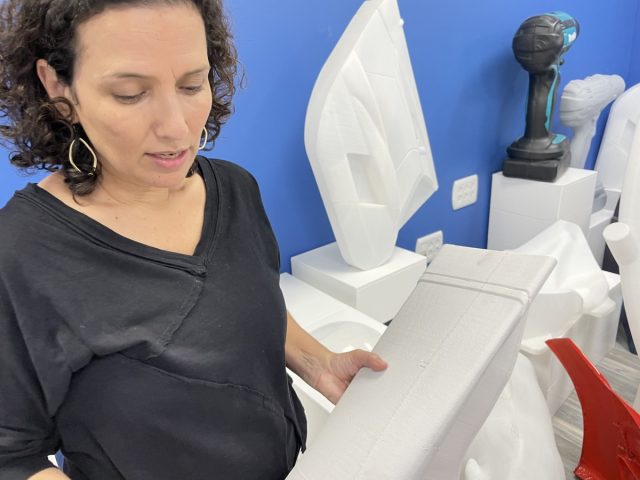

Massivit is on the opposite side of the spectrum of Israeli 3D printing. Like Stratasys, the company works with polymers, especially non-durable ones in the early days. The difference is that Massivit developed its GDP technology to produce very large parts, quickly and at relatively low costs. The GDP process works by polymerizing a resin material as it’s extruded and deposited onto a build platform in a chamber that can easily fit two full-size humans. Since the last time we visited in 2015, the company has come a long way, with an expanded office structure and several new product lines now on the market, beyond the early Massivit 1800 system. That’s in part because in February 2021 Massivit, which lists Stratasys among its investors, raised $52 million (NIS 169 million) in an IPO on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange.

With its large format modeling capabilities, Massivit began by targeting the automotive, marine, rail, furniture, advertising, and aerospace markets. Cumulatively, it has sold more than 180 printers in 40 countries worldwide and has accrued a sales volume of over $58 million as of Q3 2022. During the nine months through September 2022, Massivit sold 19 printers compared with 14 printers in the comparable period of 2021 – an increase of 36%.

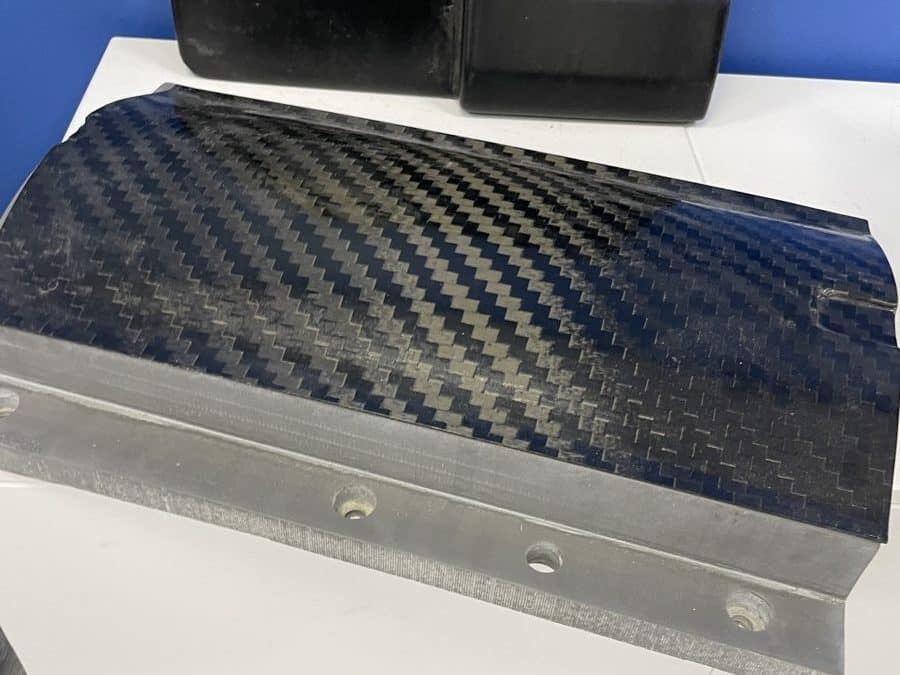

In 2022 Massivit also introduced a new technology, which it refers to as Cast in Motion in the new Massivit 10000 system, for which it has obtained 28 (non-binding) pre-orders. This process enables the direct production of highly complex epoxy tools within a break-off 3D printed shell and it could mark a revolution in the composites tooling industry. The first 3 Massivit 10000 printers were sold to customers from the aerospace (Kanfit in Israel), luxury bath ware (Lyons USA), and automotive industries (Novation Tech in Italy). A new system, the 10000-G, which enables both stand-alone GDP and Cast-in-Motion processes in the same machine, was released at Formnext.

Manufacturing on Demand

Addressing next-gen market needs

While Israeli 3D printing companies such as XJet and Massivit emerged as a spinoff of Objet’s technological knowledge base, the AM market has continued to evolve. Many operators have understood that the only direction for AM to continue growing is to address the need for scalability, higher productivity and cost-effectiveness by finding new applications where AM can guarantee a stronger value proposition than traditional manufacturing methods. Within this context, two technologies have proven most suitable to address these requirements: polymer PBF and LFAM (large format additive manufacturing).

3DM and fast laser PBF

The need for better, faster, multiple lasers in polymer PBF processes is evident for the technology to be able to cater to higher productivity markets and adequately compete with rivaling processes such as MJF, SAF and HSS (collectively referred to as thermal PBF). According to 3dpbm’s latest Polymer AM Market Report, even as thermal PBF technologies get their foothold into the PBF market, especially in terms of generated hardware revenues, laser PBF solutions will continue to represent the vast majority of units sold.

3DM intends to cater to the growing number of laser PBF companies and systems entering the market by offering a new quantum cascade laser (QCL) solution that dramatically changes the way the laser system works in the polymer PBF additive process. Unlike CO2 lasers commonly used in standard SLS processes (which require the addition of a specific material to the polymer powder in order to facilitate energy absorption), the 3DM beam head operates on frequencies that are optimal for melting thermoplastics.

This is why we are referring to this process as laser polymer PBF (LP-PBF) and not simply SLS: the 3DM beam head completely melts the powder, it doesn’t just sinter it. It can do this because the system has complete control of the meltpool. Each 3DM beam head integrates four different laser beams which converge into a single beam. Up to four of these beam heads can be integrated into a single large laser PBF system, achieving extreme speeds and precision. In addition, because the 3DM system enables the regulation of the laser frequency to obtain optimal results, it can rapidly adapt to an infinite variety of new materials, opening unprecedented possibilities for polymer PBF companies and adopters in an area (the qualification of new materials) where competing thermal PBF technologies still struggle.

Largix, bigger, better LFAM

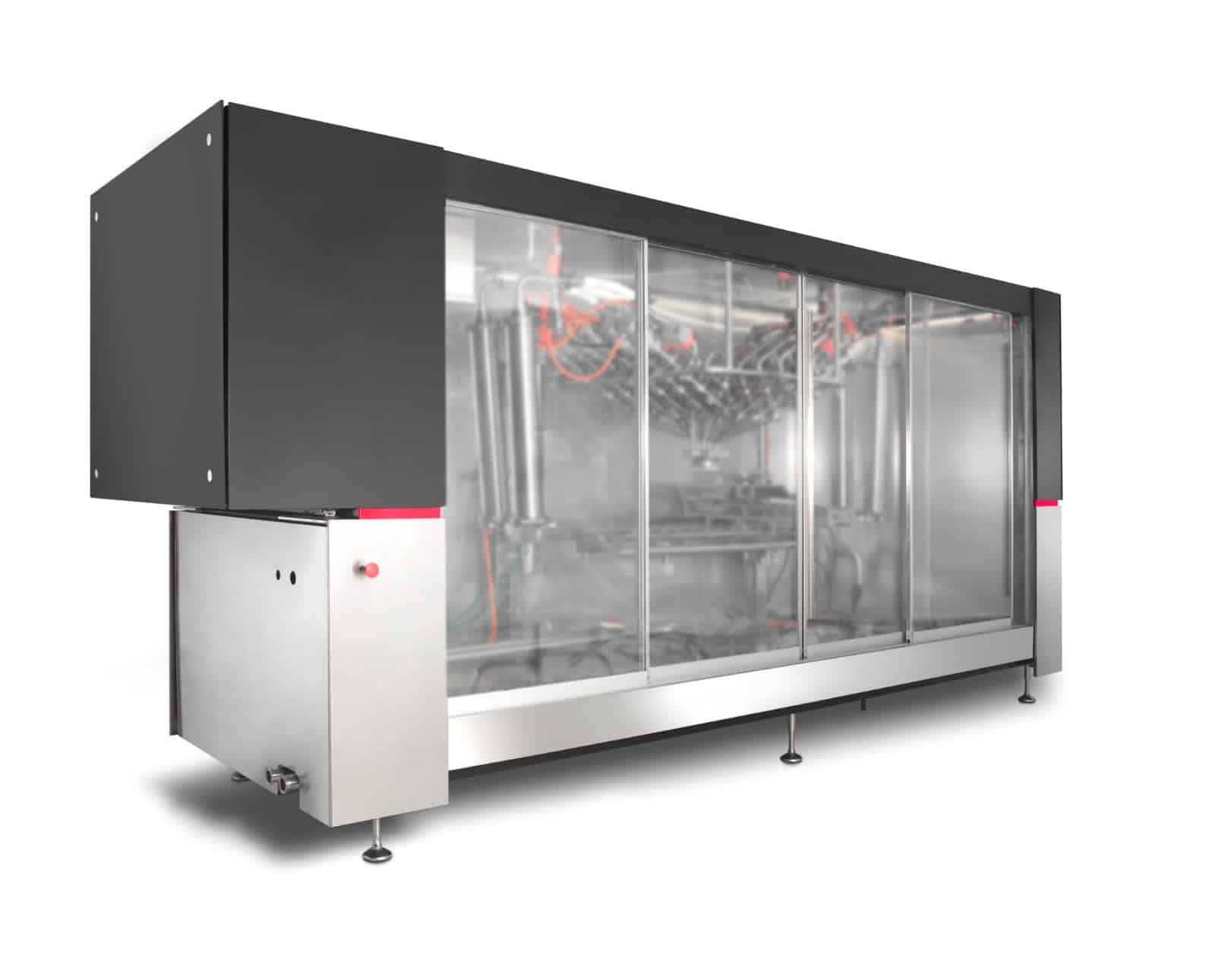

Much like 3DM (but in a very different way) Largix is using lasers to radically change the thermoplastic polymer deposition process for LFAM (large format additive manufacturing) technology and applications. The Largix system uses a relatively standard large-size gantry system and augments it with an ultra-high-tech laser extrusion printhead.

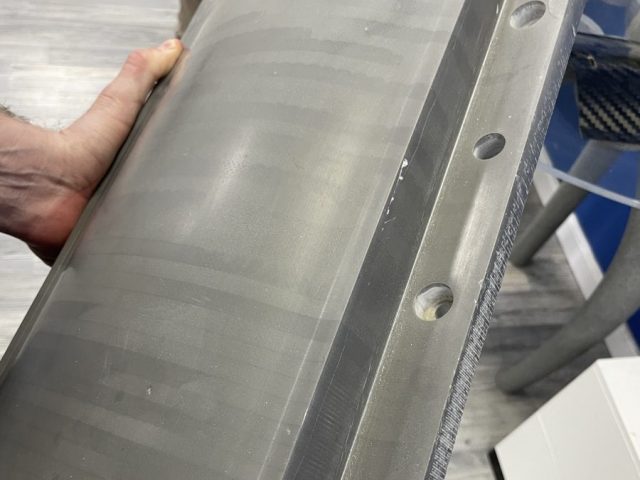

The big difference, compared to all other polymer LFAM extrusion systems on the market, is that Largix does not use pellets or 3D printing filaments and does not extrude a thick rounded layer of material. Instead, the Largix printhead uses large spools of squared-off thermoplastic material “strips”: four of these are fed into the machine at the same time and bonded together by a laser that melts the exterior surface of each strip, making them bond to the lower layer, whose surface is also melted by the laser beam and then pressed together. The result is a flat, rectangular layer that bonds perfectly to the previous one. For even better surfaces, Largix will integrate a CNC system that can cut off all excess material during the build.

This approach enables several significant innovations, that make this technology unique and very much end-use application-ready. The first is that it can use standard thermoplastics, including the most widely available and cost-effective ones such as standard polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE). The second is that most of the printable material (except its outer surface) remains relatively cold, so the process is extremely fast. Another advantage, which may seem counterintuitive, is that the layers bond more strongly than in standard extrusion due to the fact that both the previous and current layers’ surfaces are melted by the laser beam.

All these elements make Largix’s technology ideal for producing large format parts, even those that are not overly complex, in an automated and cost-effective manner. The opportunities here are as large as the technology, which is nearly infinitely scalable and we will be exploring them further in the future.

An appetite for the future

The last part of this reportage on Israeli 3D printing companies focuses on one of the most futuristic (and in many ways fascinating) potential applications of 3D printing: vegetable-protein-based or cellular-agriculture-based cultured meat production. Israel is one of the places in the world that has the highest concentration of alternative meat startups and many of these are based in Rehovot. 3dpbm has been tracking this segment for years – ever since we published our first analysis of food 3D printing in 2014 – and we’ve seen the number of cellular agriculture companies working with 3D printing technology listed in our Index grow to 19. Two of these best represent two diametrically different approaches to 3D printed meat.

Feeding the machine

Redefine Meat uses different types of vegetable-derived proteins to mass 3D print multi-material products whose texture is more complex than basic nuggets, meatballs and burgers. The company has already established a presence with commercial products in supermarkets and restaurants in Israel as well as in Northern Europe, with its largest production facility based in Holland.

The HQ in Rehovot is where the multimaterial extrusion and deposition technology is fine-tuned and new materials are tested. The production facility was off-limit during our visit but it is also located in the same building (which is the same building where XJet was originally located – before moving to the new HQ across the street in 2019).

We could not find the Redefine Meat products in the Rehovot supermarket and one restaurant in Jerusalem that was supposed to serve it told us they no longer carry it (but other ones that we could not visit confirmed that they had it). So we can’t tell you how the Redefine Meat tastes. However, the company’s business model appears fairly solid and not reliant on difficult-to-obtain cellular-based materials. Different vegetable pastes are “fed” into the machine to obtain the cuts, which are conserved in large freezers like any meat would be.

A bioprinting farm

Renting out a two-floor office in the Stratasys building is Aleph Farms, a company that is working on developing products that mimic actual meat products by integrating different cellular materials and even vascularization into its bioprinting process. This is no easy task. So far the company has managed to produce non-3D printed meat-like products that combine a vegetable protein-based scaffold and lab-grown cellular materials for true meat flavor. The cells are grown in a standard incubator and then applied to the vegetable protein scaffold.

There are many challenges in this approach and some, such as the need for bovine serum, have already been solved (no animal-derived product at all is present The biggest challenges now for Aleph Meat (and all cellular agriculture) companies are scaling cell production and scaling productivity for more advanced meat products (so products that integrate texture).

It’s impossible at this time to predict when and how they will be addressed but this is true of many new technologies. At one time this was the case for EV batteries, and reusable rockets (then Elon Musk came along) and has been – and it is still – the case for nuclear fusion (but progress is ongoing and accelerating). However, just like in all these examples, a huge demand (in this case for non-animal-derived meat) is a sufficient driver to ensure that investment will keep coming in for those companies that show progress. This progress will take place across different applications, with fully bioprinted, mass-produced, multimaterial, vascularized meat likely seen as the Promised Land at the very end of a long timeline.

In Israel, the counting of years started 5,783 years ago. What’s a few decades more?

You might also like:

Lithoz sales of LCM technology systems doubled in 2022: Lithoz co-founder and CTO Dr. Johannes Benedikt was extremely proud of his team’s achievements this year. Underlining the huge potential of combining ceramic as a powerful material with the geometric freedom of additive manufacturing, he stated that “all answers to our urgent questions of today, from aging societies to sustainability and climate change, will probably contain a 3D printed ceramic part as part of the solution.”

* This article is reprinted from 3D Printing Media Network. If you are involved in infringement, please contact us to delete it.

Author: Davide Sher

Leave A Comment