Researchers at the University of Santiago de Compostela, MERLN Institute University College London (UCL) and UCL spin-out FabRx, have come up with a way of 3D printing tablets inside of seven seconds.

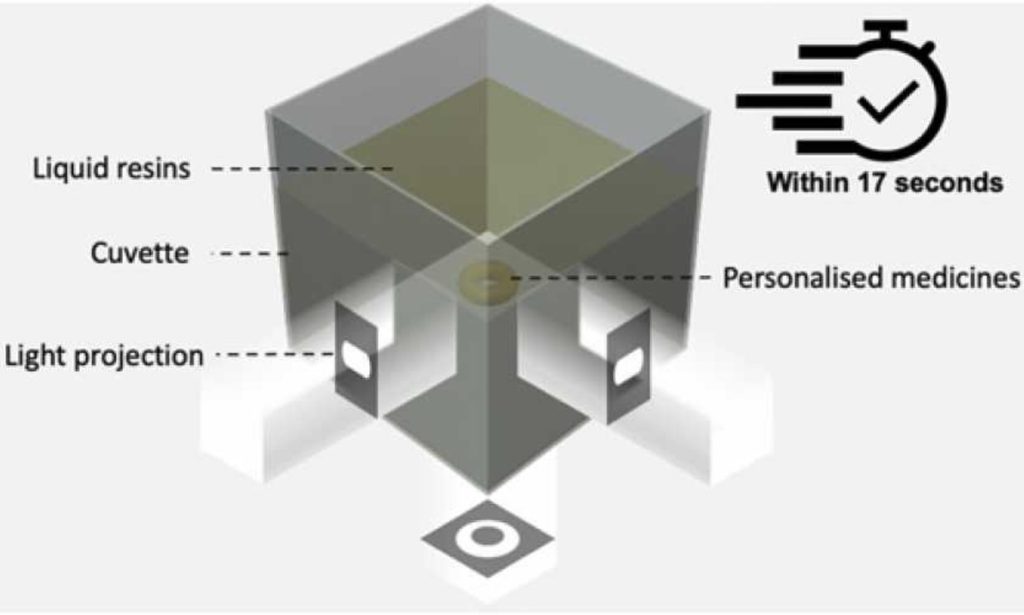

As opposed to the normal vat photopolymerization process, which can be used to print pills layer-by-layer, the team’s volumetric printing approach is capable of curing full vats of resin in a single run. In doing so, the scientists say their technology has the potential to ramp up the rate at which custom medication is produced, a USP that could prove vital to making end-use clinical 3D printing more viable.

“This could really be a game-changer for the pharmaceutical industry,” Alvaro Goyanes, one of the UCL scientists behind the project told the i newspaper. “Personalized 3D printed medicines are evolving at a rapid pace. They are starting to reach the clinic for trials and in a best case scenario they could be used in the health service in three to five years.”

FabRx’s custom medication drive

Since 2016, when Aprecia established itself as an early leader in additive manufactured medicine with the launch of fast-dissolving Spiritam, the first FDA-approved 3D printed drug, it’d be fair to say that the technology has come on leaps and bounds.

By 2020, for instance, researchers in Pakistan had proved it possible to 3D print antibiotics with optimized drug-release rates, via fused deposition modeling (FDM) technology and precise infill control. Earlier that year, a team based at St. John’s University also took a similar approach to 3D printing egg-shaped capsules, designed to be difficult to crush by those trying to abuse prescribed opioids.

More recently, FabRx itself has made advances in the field of tailored medicine as well, developing a means of Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) braille-patterned printlets for the visually impaired, as well as launching its M3DIMAKER system.

Marketed as the ‘first pharmaceutical 3D printer for personalized medicines,’ the machine features a multi-nozzle setup that allows users to switch heads and change from FDM to Direct Powder Extrusion production. The start-up also boasts that the system is supported by software that allows it to create prescribed pills on-demand, but this progress hasn’t stopped it iterating upon its technology.

In fact, working with colleagues at Universidade de Santiago de Compostela and UCL late last year, FabRx managed to develop its own smartphone-powered tablet 3D printer. Built around a modified M3DIMAKER, the team’s revised setup proved capable of producing customized blood-thinning capsules, and it was thought at the time that it could be used to improve access to prescribed medication.

Vat polymerization’s speed limit

So, given FabRx’s track record of relative success in 3D printing drugs with custom release profiles, shapes and sizes, why hasn’t it managed to achieve greater traction in the pharmaceutical sector? Well, aside from issues such as gaining regulatory approval and passing the relevant testing procedures, there’s also a commercial drawback to adopting 3D printing in this way: throughput.

According to the UCL-led team, “existing 3D printing technologies don’t afford the speeds required for the on-demand production of medicines in fast-paced clinical settings.” However, the scientists add that volumetric printing “exploits the threshold behavior” that occurs in polymerization to cure masses of resin, hence it may offer a solution to this.

Manufacturing on Demand

Now, building on the work carried out in their previous study, the researchers have found a way of putting this approach into practice, by manipulating light in such a controlled way, that it can solidify vats of resin simultaneously. This is said to have been achieved by tweaking the intensity of emitted rays and applying them at various angles, until the full mass of material can be polymerized in one go.

Volumetric 3D printing in-action

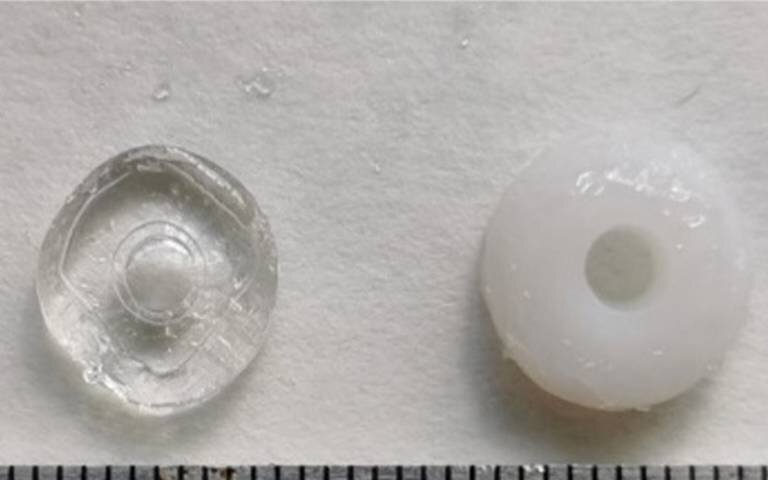

During their study, the researchers deployed a modified 3D printer to assess the efficacy of their revised approach, and produce tablets from six different photoinitiator-loaded resins, with paracetamol being used as a model drug. Initial results from these tests showed that the team were able to produce tablets with tunable drug release profiles, at a rate of anything from 7 to 17 seconds per pill.

With further development, the scientists say that their approach could be used to create ‘polypills’ at pace, the likes of which incorporate tailored doses or multiple medications, but tend to come with longer lead times. One application the technology is currently reportedly being trialed in, involves 3D printing cancer therapy and anti-side-effect drugs inside the same pill at a French hospital.

“To reduce the risk of recurrence, many women with early-stage breast cancer are treated with hormone therapy for five years, often with additional treatments to manage side effects,” Maxime Annereau, the Gustave Roussy hospital pharmacist leading the project explained to the i newspaper. “Taking all of these treatments in a single 3D printed tablet with a personalized dose should make it easier to complete the treatment.”

Another potential application of the technology lies in the production of more appetizing medication for poorly kids, especially given that London’s Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital is said to be weighing up installing a 3D printer at its pharmacy, with its team of specialists there believing that the technology could, in future, become an essential piece of kit.

“I am already looking to put a 3D printer in the pharmacy at GOSH to support trials of use of 3D medicines,” Steve Tomlin, Chief Pharmacist at the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital also told the newspaper. “Knowledge of genetic differences in people’s responses to medicines (pharmacogenomics) means that we know that for many drugs one size does not fit all.”

The researchers’ findings are detailed in their paper titled “” The study was co-authored by Lucía Rodríguez-Pombo, Xiaoyan Xu, Alejandro Seijo-Rabina, Jun Jie Ong, Carmen Alvarez-Lorenzo, Carlos Rial, Daniel Nieto, Simon Gaisford, Abdul W. Basit and Alvaro Goyanes.

* This article is reprinted from 3D Printing Industry. If you are involved in infringement, please contact us to delete it.

Author: Paul Hanaphy

Leave A Comment