When AM, especially metal AM, broke onto the global manufacturing scene and became understood as a technology that could be used to make final parts—not just prototypes—with fewer or no geometric restrictions, engineers around the world began to understand that they had to rethink the way they designed these parts. This concept became known as DfAM, an acronym for Design for Additive Manufacturing. As VELO3D becomes the first new entry in the metal powder bed fusion segment to truly scale, with revenues of nearly $100 million expected in the next fiscal year, and makes it to the NYSE (VLD) after the merger with billionaire Barry Sternlicht’s SPAC company JAWS Spitfire, CEO Benny Buller tells us that we need to move away from “obsolete and abused concepts such as DfAM and workflow automation if we want AM to really live up to its promise”. As disrupting manufacturing paradigms is exactly what AM has been doing since the start, this sounds like something we want to hear more about.

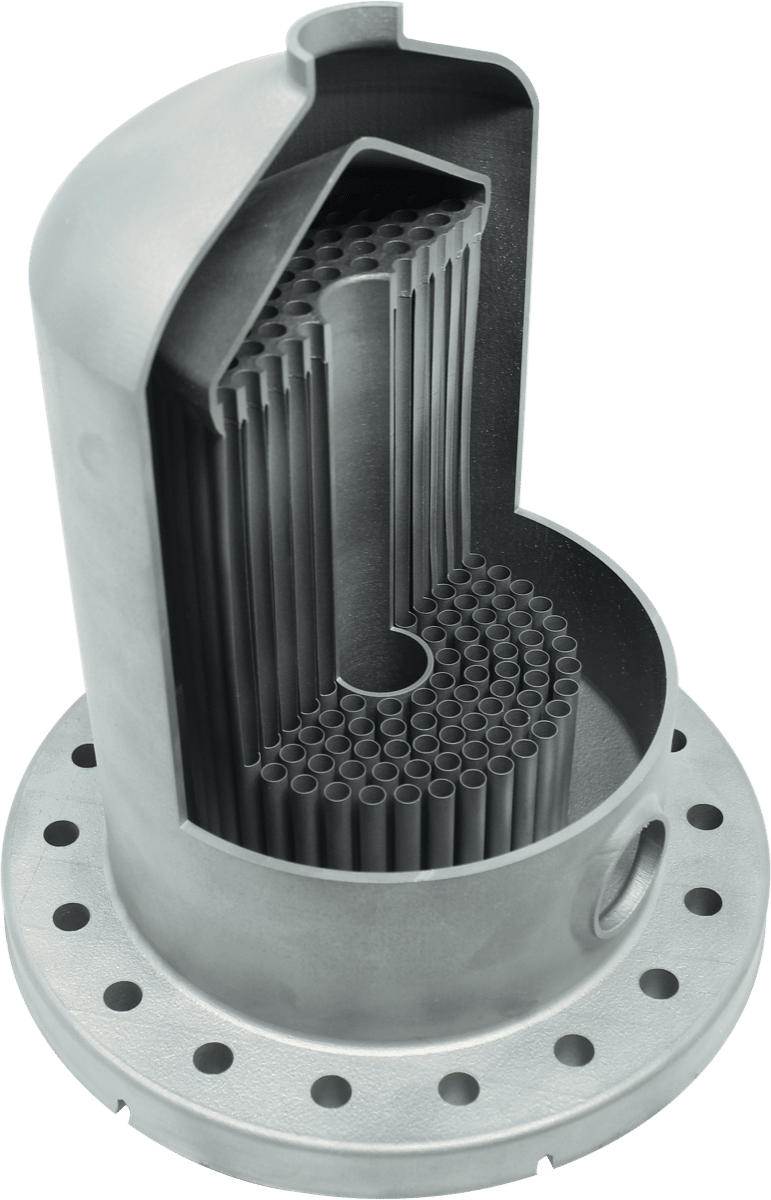

“We need to free AM from the constraints of this idea, which has done more damage than good to AM as a whole,” Mr. Buller confirms. “The idea of DfAM has come to be associated with generatively designed structures that remove material to create complex lightweight and topology optimized geometries. To a certain extent, this can be achieved with CNC technology, which is a much more mature and ready-to-use digital manufacturing process. What AM should be used for is parts that cannot be produced by CNC or any other method, and by that, I mean parts that have complex structures, such as internal channels or expensive multi-component subassemblies, in one piece. This is where the benefits of AM are clearest, but the reality is that most metal PBF technologies cannot make these parts.”

What Benny Buller is referring to is the fact that all the metal PBF processes that have been used for the past 20 years require supports, during the build, that are very hard to remove. This means that, if an internal structure has an overhang of a certain angle, it cannot be produced by a “traditional” metal PBF process. The ability to produce advanced parts by metal PBF without using supports is how Velo3D was able to stand out from competitors, even as a startup. The company has already attracted major aerospace customers such as SpaceX, Aerojet Rocketdyne, Raytheon and Honeywell, as well as innovative startups such as Boom Supersonic and Launcher, who have put in orders of Velo3D’s Sapphire 3D printers for several tens of millions, with more likely to come.

The genesis and industry’s reaction to Velo3D’s support-free metal PBF capabilities was initially disbelief, followed by the realization that these capabilities will need to be implemented for AM to move forward. “When we came out of stealth and showed our capabilities the initial reaction was: ‘it’s impossible. Then they saw it was possible but said there was no way it would be cost-effective,” Benny Buller remembers. “Eventually our competitors understood it could be done and said that they could not only do it as well but also do it on the same machines that had been used for two decades.”

Mr. Buller does not think that other metal PBF hardware OEMs can implement the same capabilities, which are based on advanced hardware-software-manufacturing process combination, powered by AI. On 3D Printing Media Network we have covered extensively the way the VELO3D system works (see this 2019 interview with VELO3D’s Richard Nieset for more details) and I can admit that I – like most of the AM industry – was very much impressed by the first videos released by the company, showing a support-free complex part emerge from the powder bed. However, this is not the only disruption that Benny Buller is looking to bring to the metal AM industry.

Manufacturing on Demand

His vision for future growth is clear and very focused, which is something challenging to do in AM. He has identified metal AM as the major revenue opportunity, metal PBF as the current and future dominant metal AM technology, and the aerospace segment as the biggest adopter. For the foreseeable future, he expects that metal AM will be used to produce small batches of very complex, advanced aerospace parts and components. By using VELO3D’s technology he argues that this will be done in a much more affordable and rapid way than with any other manufacturing process, especially when it comes to internal channels and subassemblies.

So, the next question is: how big can AM get? “As a former electronic engineer”, Mr. Buller says, “I am used to thinking in terms of Moore’s law and I expect that something similar in terms of the evolutionary curve will also take place in AM, as a digital manufacturing process.” However—he concedes—there are many aspects and challenges of metal AM that need to be improved and addressed for the technology to scale in terms of adoption. These include materials, part quality and especially standardization and repeatability: a part produced by AM anywhere in the world by any company needs to be the same as that part produced anywhere else. This is true both for external suppliers and internal company networks.

This is something that VELO3D engineers also set out to do by developing sensing and feedback loops that make it possible to continuously monitor and automatically correct variables as you go through the build. This enables the system to work in a serial production environment—repeatable, from machine to machine. With these capabilities in place, Mr. Buller expects that major aerospace customers could eventually build metal AM digital production fleets of 10 to 100 internal machines. However, this is not the only way he sees his company scaling up.

“In our vision, even the largest aerospace clients will implement supply-chain-based solutions for their AM production requirements to complement internal production capabilities, he says. “We intend to build a production network by leveraging the largest suppliers of CNC services, who will begin implementing and complementing their offer with metal AM capabilities. These networks will be based on companies that will have fleets of 20 and more machines around the world. By ensuring part repeatability to the levels that CNC technology can, we expect AM to live up to its promise.”

To do this, and to continue to build and expand its customer base, Mr. Buller argues that his company does not need any major technological breakthrough. The technology is ready and will be progressively and predictably evolved to meet growing demand. “Eventually we will get to the point where we say ok, we got it down, and then it will be all about cost reduction and productivity increase.” For Velo3D the next product evolution is called Sapphire XC. This “extra capacity” system has up to five times higher throughput compared to the original Sapphire system and the ability to reduce cost-per-part by up to 75%. The new system is also substantially larger than the Sapphire metal 3D printer, with a build volume of 600 x 550 mm (vs 315 x 400 mm and eight 1,000W lasers.

In a recent interview with a major financial network, Benny Buller said that, although he has received high-profile offers, he has no intention of selling the company. Velo3D—he explained—is his life’s work and he intends to build it into a major public company that will enable many other companies to produce parts in a better and faster way. If this is the premise, the sky is literally the limit.

* This article is reprinted from 3D Printing Media Network. If you are involved in infringement, please contact us to delete it.

Author: Davide Sher

Leave A Comment