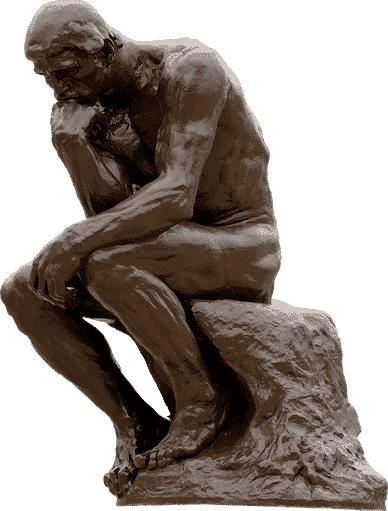

Bronze pieces by Donatello, Auguste Rodin, Henry Moore and other great sculptors of the past are still captivating the imagination of a modern viewer. Prominent contemporary sculptors like Brian Booth Craig, Coderch & Malavia, and Grzegorz Gwiazda follow in the footsteps of their legendary predecessors in creating beautiful works that will be appreciated for centuries to come. And while we don’t cease to admire the ingenious compositions and intricate modeling, not many viewers today realize how much hard work goes into the production of sculpture.

Since a sculptor’s practice necessitates a great deal of effort in addition to the direct creative process, Alexandra Slava believes that a better understanding of the technical side will only increase the general appreciation of sculpture as an art form. Based on my own experience as a traditional sculptor, I would like the focus of this article to be on one of the most common methods of sculpture production, namely the lost-wax bronze casting technique.

Despite the constant technological modernization of all areas of life, most traditional sculptors, whose methods include the use of plastic materials such as wax or clay, continue to adhere to the ancient labor-intensive process of replicating the original models in a more permanent form, e.g. bronze or other metal alloys. Bronze, in particular, is still held in high regard as one of the noblest mediums of sculpture, sought after by artists and appreciated by collectors and the general public. The technique of lost-wax casting (also called “investment casting”) is still commonly used to reproduce both intimate indoor sculptures and large monuments. It entails several sequential stages of development.

Traditionally, the work on a piece of sculpture begins with a small-scale preliminary maquette, in which an artist visualizes the idea and determines the general composition. The maquette also serves as a model for designing a full-scale armature, i.e. wooden or metal framework around which the sculpture is built. The armature provides stability and structure, necessary to support the weight of modeling material. Therefore, a poorly designed framework can result in an unfortunate interference with the artist’s concept, or worse, the utter collapse of a work in progress. After the armature is built, a sculptor gradually covers it with pliable material adding and subtracting masses to find the desired shape. This is when the act of artistic creation takes place. Following the completion of the modeling stage, the positive original is then converted into the negative mold, i.e. a hollow cavity with an exact impression of the sculpted form to be reproduced in a more durable material. In addition, the process of molding gives a sculptor the opportunity to produce multiple copies of the same piece in limited or open editions.

Molding itself is an elaborate multi-stage process approached in a variety of ways. In the past sculptors used either waste-mold or piece-mold methods, optimized today by the use of silicone rubber applied directly on the surface of the finished positive original. When cured, the silicone forms a flexible layer containing an accurate negative imprint of the form.

The silicone layer is then covered with segments of a rigid outer shell that retain its shape during the later stage of casting. This supporting shell, commonly known as mother mold, needs to be divided into sections in a way that avoids the formation of undercuts which may obstruct the further process of demolding. In case of a composite form, the sculpture is divided in multiple parts, each requiring a separate mold. For example, a sculpture of a standing human figure is usually split in half into lower and upper sections with a head, arms, hands and even individual fingers taken apart and molded separately. As a result, the mold of a complex sculpture may consist of dozens of parts, each one of which is further divided into sections of the rigid shell. Subsequently, the silicone layer is cut in half along the seam line, peeled away from the original and placed into the mother mold. The positive original itself is often damaged or completely destroyed during this process.

The finished molds are typically quite large and heavy. Modern sculptors who produce their works in bronze and other metal alloys depend upon foundries, i.e. establishments specializing in metal casting.

Most foundries offer professional molding services. However, that incurs comparatively high costs. For this reason, many sculptors elect to make molds independently and then transport them to a foundry. The transportation, of course, implies additional expenses. Due to high production costs and labor intensity involved in the molding process, most sculptors tend to hold on to the used molds keeping them in their own studios or foundry storage facilities. The intention is to have the negative imprint at hand in case another copy of the positive is needed, until the established number of copies in the edition is reached. Unfortunately, no matter how good the quality of materials, molds deteriorate with time and usage, so the later casts require extra work to bring back the qualities of the initial original.

When the wax positive is approved, it is fused with multiple “gates”, i.e. channels, through with the molten bronze will flow and trapped gas will escape during the later stage of pouring. After gating the wax is embedded in another rigid mold, referred to as investment. It is formed by either heat-resistant plaster or ceramic shell that is placed in a high-temperature kiln for dewaxing. During heating, the wax melts and escapes the shell leaving an inner negative void. The name “lost-wax casting” originates from this stage of the process. Molten bronze is then poured through the gates into the shell. When cooled down, the investment is removed revealing the raw bronze positive. The gates are cut away and the surface of the piece is sandblasted, i.e. cleaned with fine abrasive sand projected by compressed air. In the case of a larger sculpture with several sections poured separately, the assembly needs to be executed by the process of welding. The weld line and other imperfections are then refined with the help of metal chasing tools.

In the final stage the bronze piece is patinated through the chemical application of color with heat on metal surface. A successful patina compliments the texture, form and overall character of a sculpture. The last step is to apply a coat of wax to preserve the achieved color. Patination is an art form within itself that requires extensive knowledge and experience.

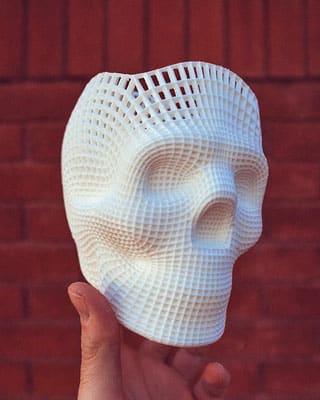

Thus, the journey from the conception of a sculpture to its final material realization is burdened by many technical processes that are costly and time-consuming. Furthermore, it puts apparent limitations on creative aspirations of an artist. As we do live in the era of innovation, the question arises whether there are any ways in which the modern technologies could optimize a sculptor’s workflow and productivity. As might be expected, the intersection of sculpture and computer science already does exist and is rapidly forming an independent interdisciplinary field. Similar to the introduction of Photoshop to the art of photography and illustration, 3D printing technologies and digital programs are catalyzing the transformation of the three-dimensional art. Sculptors today are incorporating digital tools by means of various sculpting software and through the use of 3D scanning and printing methods.

As a classically trained artist loyal to the physical act of creation, I am more interested in using the technologies as a way to enhance the reproduction of traditionally modeled sculptures in durable materials such as bronze. By 3D scanning the original piece and then printing it directly in the wax filament, a sculptor is given the opportunity to eliminate the laborious and time-consuming process of mold making. In addition, 3D scans can be indefinitely stored as digital files without the risk of their deterioration, as is the case with physical molds. After scanning a sculpture, an artist may use 3D sculpting software to make necessary adjustments and electronically send it to a foundry for bronze casting. In the case of monumental sculptures, the model might be initially developed on a smaller scale, 3D scanned, digitally manipulated, and printed in the required size. The sculptors adopting such a method, by all means, become more efficient and competitive. The other benefits of employing digital tools at various stages may include smart solutions for designing and building armatures, creation of digital maquettes, and visualization of finished works installed at specific sites.

Despite the convincing arguments in favor of implementing available technologies in the sculpting process, a bigger part of the traditional art community remains skeptical about the capacity of digital tools to fully transmit the impression of human touch or, more specifically, to capture the intricate textures, tool marks and fingerprints intentionally left by the artist. Indeed, the traditional approach of molding the sculpted piece, however effortful and costly, might still be incomparable in regard to that level of precision. Thus, the goal is to refine technologies to meet the high standards of the art community and to encourage traditional artists to venture into the digital realm. Ironically, the improvement is only achievable through joint efforts of the two philosophically opposing approaches. But in the long run, the intersection of traditional art and computer science is directed at mutual enhancement of various fields that will surely have significant implications in the future.