The Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) has announced the first recipients of its Personalized Regenerative Immunocompetent Nanotechnology Tissue (PRINT) program. The selected research teams from Carnegie Mellon University, Wake Forest University, the Wyss Institute, University of California San Diego, and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center will develop advanced bioprinted organs, including livers and kidneys, designed to function without immunosuppressive drugs by using patient-specific cells or those from biobanks.

The initiative aims to produce human-sized, fully functional organs within hours, addressing the urgent shortage of transplantable organs in the United States, where thousands of patients die annually while waiting.

“Developing universally matched organs has never been done before in the history of transplantation. Printing a precisely matched, functional human organ will fundamentally change what is possible in transplant medicine and will save countless lives,” said Alicia Jackson, Ph.D., ARPA-H Director. “Through the PRINT program, ARPA-H will strengthen U.S. leadership at the frontiers of biotechnology and biomedical innovation.”

Technical Ambitions and Program Goals

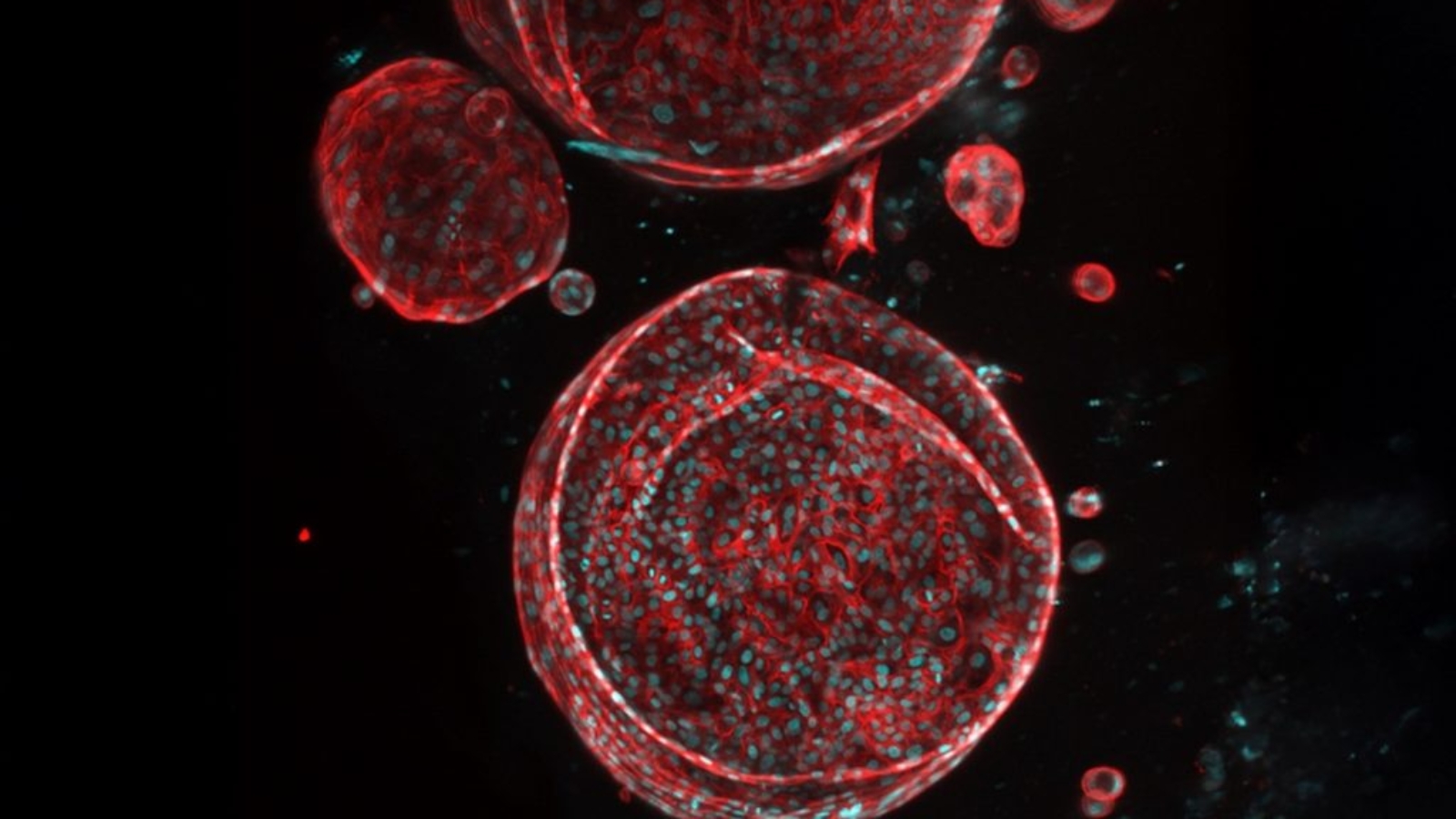

PRINT seeks to accomplish what has long been unattainable in tissue engineering: creating human-sized organs complete with cells, blood vessels, and supporting tissue capable of performing the essential functions of kidneys, livers, and other organs. If successful, these initiatives could pave the way for regenerative solutions for other challenging organs, such as the pancreas and lungs.

The program carries a total budget of up to $176.8 million over five years. Funding is awarded as performer awards rather than traditional grants or contracts, contingent upon each team meeting aggressive milestones.

“What we are trying to do with PRINT is extraordinarily hard. It requires major breakthroughs in cell manufacturing, bioreactor design, and 3D printing technology to reliably build organs that function like the real thing,” said PRINT Program Manager Ryan Spitler, Ph.D. “But if we succeed, we won’t just be giving patients faster access to new organs—we will change the foundation of transplantation itself. The advances from this program could dramatically reduce wait times, eliminate the need for lifelong immunosuppressive drugs, and open the door to bioprinted solutions for many other organs in the future.”

Research Teams and Their Objectives

Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh will focus on developing cost-effective, immune-compatible bioprinted livers for acute liver failure, aiming for first-in-human trials within five years and eventually addressing all forms of liver failure.

Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem is working to produce clinical-grade, vascularized renal tissue to augment kidney function, validating their approach through preclinical trials alongside a commercialization strategy to reduce donor shortages.

At the Wyss Institute in Boston, researchers are engineering universal, clinical-scale liver tissue from adult stem cells to overcome current tissue fabrication challenges and create implantable tissue for patients with liver dysfunction.

University of California, San Diego is developing scalable, patient-specific bioprinted livers tailored to an individual’s anatomy and physiology, eliminating the need for donor organs or immunosuppressants while ensuring long-term functionality.

Manufacturing on Demand

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas aims to produce transplantation-ready livers capable of fully restoring function, including integrated blood vessels and bile ducts to support metabolism.

Limits and Challenges

Creating functional, human-sized bioprinted organs is extremely challenging. Replicating complex tissue structures, including blood vessels, bile ducts, and other microfeatures, pushes the limits of current 3D printing and tissue engineering. Printed organs must perform reliably under real physiological conditions, requiring further advances in cell manufacturing, bioreactors, and tissue integration.

Immune compatibility is another major hurdle. Even with patient-derived or biobank cells, organs must remain viable without triggering rejection. Scaling production adds pressure for precise, repeatable printing, robust quality control, and standardized protocols. Regulatory approval is a high barrier, as the first transplantation-ready organs will need thorough validation by the FDA and other authorities.

Cost and accessibility are also critical. Producing organs rapidly and safely at scale must be balanced with affordability to truly reduce the thousands of deaths caused by donor organ shortages each year.

Advances Enabling Patient‑Specific Bioprinting

Bioprinting with patient-derived or biobank-sourced cells is gaining traction because it directly addresses two key barriers in transplantation: immune rejection and organ scarcity. Traditional donor organs are limited, geographically constrained, and require lifelong immunosuppressive therapy. By creating tissues tailored to a patient’s biology, researchers can reduce rejection risk, improve long-term function, and potentially eliminate the need for chronic immunosuppression.

Progress in this area is emerging across the bioprinting community. For example, Matricelf has licensed a 3D bioprinting method that combines patient-derived stem cells with extracellular matrix to fabricate implants for tissue and organ regeneration. Similarly, researchers at Utrecht University developed GRACE, a 3D bioprinting system that uses real-time imaging to optimize cell placement and produce tissues with enhanced vascular networks and multi-layered architecture, key features for building larger, patient-specific organ constructs.

Together, these examples show how personalized cell sources and improved bioprinting methods are reducing technical barriers in assembling complex tissue architectures.

You might also like:

MIT Introduces MagMix to Reduce Cell Settling in 3D Bioprinting, Addresses Key Limitation: The project received support from MIT’s Safety, Health, and Environmental Discovery Lab (SHED), which provides technical infrastructure and interdisciplinary expertise for scaling lab innovations. “MagMix is a strong example of how the right combination of technical infrastructure and interdisciplinary support can move biofabrication technologies toward scalable, real-world impact,” says SHED founding director Tolga Durak.

* This article is reprinted from 3D Printing Industry. If you are involved in infringement, please contact us to delete it.

Author: Paloma Duran

Leave A Comment