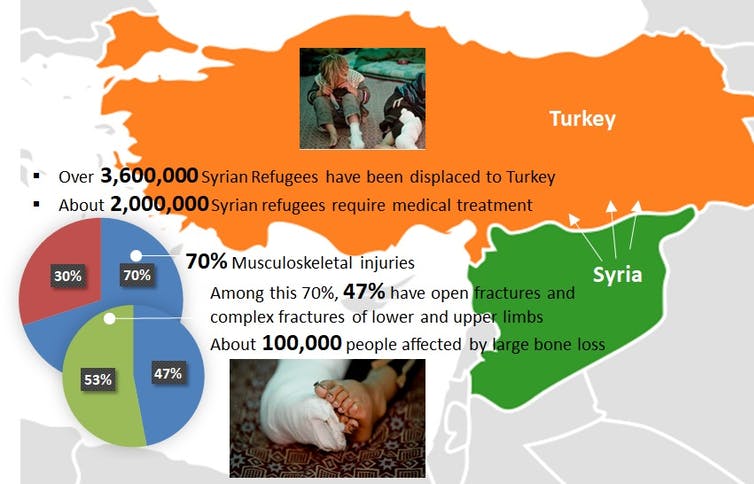

Researchers from the University of Manchester have developed a simple and cheap method for repairing broken limbs using 3D printed “bone brick”, in response to the need for urgent medical care in Syrian refugee camps.

With thousands of Syrian refugees suffering from horrific blast injuries after being hit by barrel bombs and other explosives in their war-torn homeland, many are left without access to the necessary medical care due to the collapse of the healthcare system. As such, the only option is often amputation.

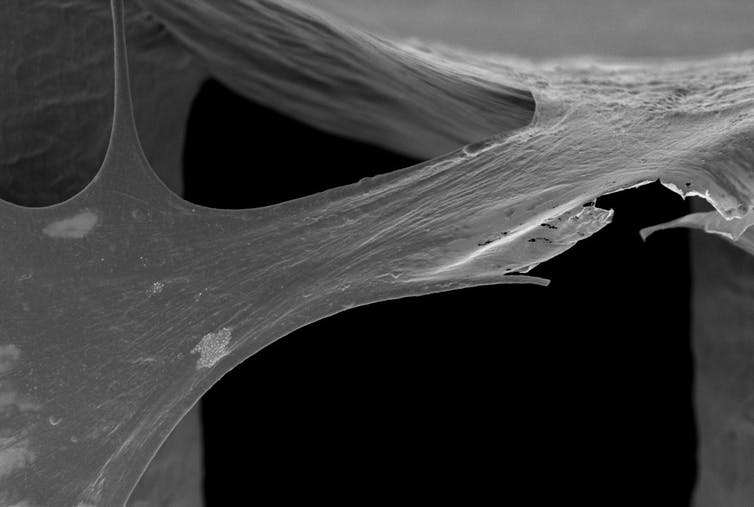

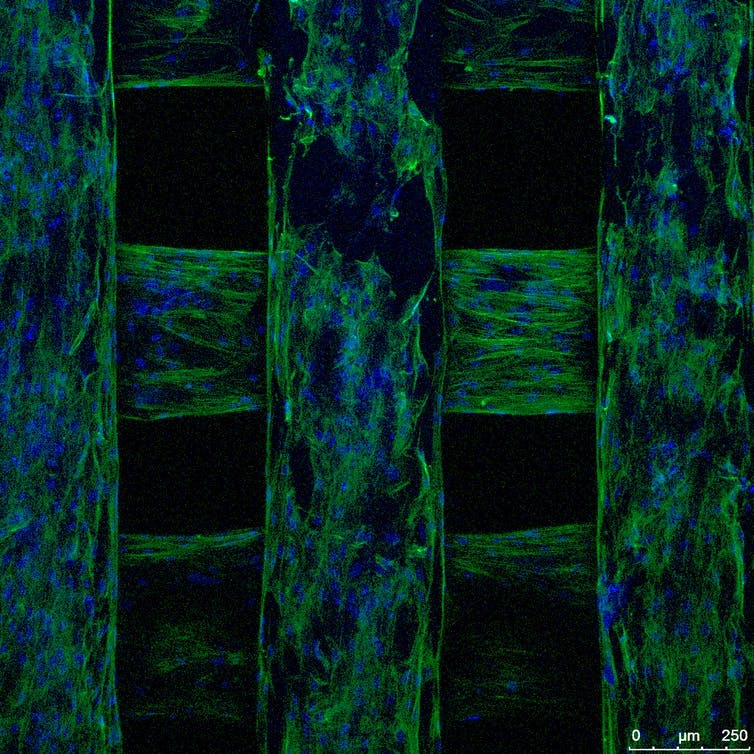

A team at the University of Manchester, led by Paulo Bartolo, Chair Professor on Advanced Manufacturing, have developed a temporary 3D printed “bone brick” – made up of polymer and ceramic materials – to fill the gaps left by blast injuries. The bricks can be clicked together to enable adequate fitting, and are degradable; subsequently allowing new tissue to grow around them. As it dissolves, the structure will support the load like a normal bone while inducing the formation of new bone.

Creating a simple, low-cost solution for medical prosthesis

Barrel bombs have caused a significant amount of destruction, misery and pain for Syria and its civilians since the conflict began. At the start of 2018, Amnesty International reported that barrel bombs had killed more than 11,000 civilians in Syria since 2012, injuring many more.

If one survives a blast, their limbs remain at risk of suffering a large, usually jagged break. Such injuries are a major challenge to repair even in the best conditions, where there is access to a fully equipped, state-of-the-art hospital with expert orthopaedic surgery and expensive aftercare. However, refugee camps are the daily reality for many Syrians, and these camps are far away from any sophisticated surgical intervention, meaning that amputations are the most likely outcome in many of these cases.

Inspired by the plight of Syrian refugees, Bartolo and the University of Manchester team invented an accessible process for helping those people in need of urgent medical care. Bartolo, having grown up in Mozambique in South-East Africa in 1968 during the middle of the war of independence, explains that he recognizes the ongoing misery and pain in the Syrian civil war.

The idea for the 3D printed bone bricks came about when Amer Shoaib – a consultant orthopaedic surgeon at Manchester Royal infirmary – visited the University of Manchester to discuss his experience in treating these injuries in Syrian refugees at camps in Turkey. “He told us that in Syria the after-effects of blast injuries were sometimes untreatable because of the constant risk of infection. The collapse of the healthcare system has also led to many treatments being done by people who are not, in fact, trained medics,” explains Bartolo.

Bartolo and his research colleagues Andy Weightman and Glenn Cooper decided to help and apply their expertise, with Bartolo’s academic interests centering on biofabrication for tissue engineering with 3D printing. With current grafting techniques holding several limitations, including risks of infection and further injury, Bartolo and the team also had to consider other factors due to the nature of the situation in Syria. “We had to consider […] making the scaffolds even more cost-effective and usable in demanding environments where it is very difficult to manage infection,” comments Bartolo.

The team opted to use 3D printing as a low-cost solution for creating bone bricks, integrated with a degradable porous structure into which an antibiotic ceramic paste can be injected. Not only does the bone brick prosthesis and paste prevent infection, it also encourages bone regeneration and establishes a mechanically stable bone union during the healing period. Having secured the backing of the Global Challenges Research Fund, the team travelled to Turkey to continue developing the prosthesis and to help the Syrian refugee community over there, meeting with academics, surgeons and medical companies who have been dealing with the refugees and their injuries firsthand. This ensured the shape and design of the 3D printed bone bricks aligned as closely as possible to the needs of the frontline clinicians.

Manufacturing on Demand

The team is also developing software to enable clinicians to select the exact number of bone bricks with the specific shape and size and information on how to assemble for a particular bone defect. According to Bartolo, “the bone brick solution is much more cost-effective than current methods of treatment. We expect our limb-saving solution will be less than £200 for a typical 100mm fracture injury. This is far cheaper than current solutions, which can cost between £270 and £1,000 for an artificial limb depending on the type needed.”

Now entering the final stages of the three-year project, Bartolo and the team have evaluated the bone bricks using computer simulation, created prototypes using 3D printing in the lab, and conducted in-vitro testing of mechanical and biological characterisation of the bricks. The next step is animal testing to prepare the device for regulatory approval, before the project will be ready for trials on human patients.

Providing aid in Syria with 3D printing

3D printing has been utilized in numerous ways to help provide aid to those in need in the Syrian civil war.

In 2018, Syria Relief, a UK-based charity working in Syria, pleaded to the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) to provide funding for 3D prosthetics for children. Traditional methods of making prosthetics are costly and time-consuming. Currently, it takes five days for the charity to make a prosthetic. The doctors working on the relief effort believe that the need of prosthetics in Syria can be met with a one off investment in 3D printers to make the prosthetics.

Additionally, Italian 3D printer manufacturer WASP has also donated an artificial limb 3D printing laboratory to the University of Damascus in Syria, to help those suffering in conflict.

Outside of medical care, 3D printing has also played an integral role in preserving key historical sites that have been destroyed in Syria, including the Arch of Triumph at Palmyra, a gateway to an ancient Semitic city with Syriac, Greek, Roman and Arab heritage.

* This article is reprinted from 3D Printing Industry. If you are involved in infringement, please contact us to delete it.

Author: Anas Essop

Leave A Comment