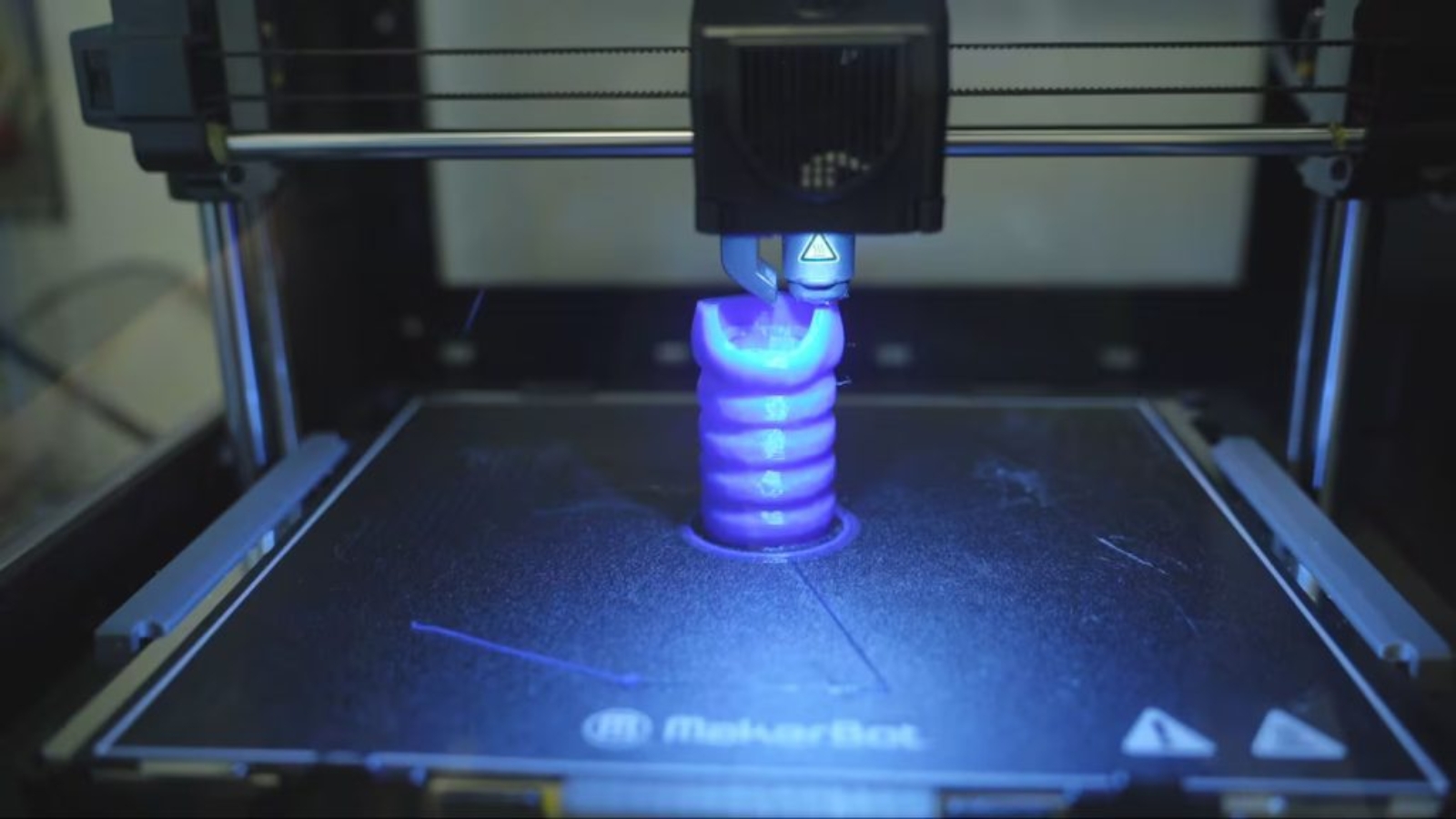

Researchers from McGill University Health Centre Research Institute (RI-MUHC) are using virtual reality (VR) and 3D printing to study whether damaged lungs could one day be repaired rather than replaced through transplantation.

In one of the institute’s laboratories in Montreal, the team is using VR headsets to examine detailed digital models of lung anatomy, moving through airways to identify damaged areas and plan where 3D printed, hollow components could be used to connect healthy sections of the organ.

Compared with organs such as kidneys or hearts, lungs are more difficult to transplant and have poorer outcomes. At the same time, respiratory disease is becoming more common due to factors including longer life expectancy and environmental conditions, while the supply of suitable donor lungs remains limited.

Led by Dr. Darcy Wagner, an MUHC researcher and Canada Excellence Research Chair in Lung Regenerative Medicine, the group is focusing on targeted interventions, producing what are essentially structural bridges intended to bypass non-functioning tissue.

Engineering around biological constraints

According to a news report, the idea for the project dates back to Wagner’s time in Munich, Germany, where early experiments were used to test whether complex internal geometries could be produced reliably.

In one of those tests, the team printed a structure shaped like a pretzel, which served as proof that the materials and process could create hollow, branching forms similar to those found in the respiratory system.

To make the approach viable in living tissue, the group had to develop its own printing materials. The inks now in use are formulated specifically for the lung and are not intended for applications in other organs such as the heart or skin.

Despite the progress, technical limits remain a central challenge. Some of the structures involved in gas exchange in the lung are only about 1 μm in size, well below what current printers can reproduce. Thus, the strategy is to print larger guiding structures and rely on the body’s own cells to complete the finer architecture after implantation.

The project remains in an early, preclinical phase. While earlier transplant experiments have produced results suggesting the concept could work biologically, Wagner said blood vessels from the recipient were able to grow into the implanted grafts. The work has not yet reached the stage of human trials.

Advances in lung tissue bioprinting

Manufacturing on Demand

Fully functional bioprinted lungs have yet to be realized, but researchers continue to advance lung tissue models used to study disease and evaluate new therapies.

Previously, McMaster University-spinout Tessella Biosciences developed a bioink that enables 3D printing of soft lung tissue that can expand and contract like real lungs while remaining stable at body temperature.

Unlike many existing bioinks that require cold conditions and lose shape after printing, the material produces flexible, stretchable structures in under an hour and maintains form at physiological temperatures. The bioink works with standard laboratory bioprinters and is intended to support more realistic in vitro models for studying respiratory disease and testing therapies.

Another notable example came from University of British Columbia’s Okanagan (UBCO) campus researchers who bioprinted a lung model that integrated airway epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells within a scaffold containing functional vascular channels.

The structure was fabricated using a PEGDA-GelMA (80:20) hydrogel with a Young’s modulus of 10.7 kPa, matching the mechanical range of native lung tissue and supporting high cell viability. This model enabled fluid perfusion, showed correct cellular organization, and generated disease-relevant inflammatory responses to cigarette smoke extract, providing greater physiological realism than conventional non-vascularized in vitro systems.

You might also like:

Wounds Could Now Be Treated Using A Closed-Loop Drug-Delivering Dressing: Having seen contributions from West China Hospital of Sichuan University and The Chinese University of Hong Kong, the research describes a 3D printed patch built around microscopic needles with tiny barbs that help the device stay in place during long periods of wear. Chronic wounds, such as diabetic ulcers and pressure sores, are a growing burden in many health systems. They often need frequent inspection, and removing dressings to check healing can itself slow recovery or cause new injury.

* This article is reprinted from 3D Printing Industry. If you are involved in infringement, please contact us to delete it.

Author: Ada Shaikhnag

Leave A Comment