In court hearings, jurors must fully understand the case so that they can make the most informed decision which is crucial. Researchers at the Cranfield Institute of Forensic Medicine in the UK believe that 3D printed models can provide a solution that is better than 2D photos or digital 3D visualization.

In a recent study, a team from the institute found that 3D printed models used in a mock court environment can help mock jurors improve their understanding of technical language by up to 94%, compared with 79% with photographic images.

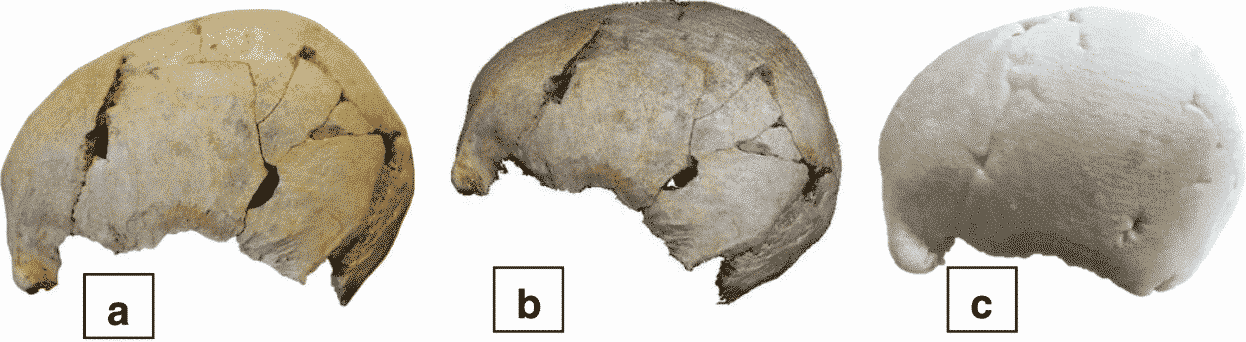

In the experiment, 91 mock jurors were randomly assigned one of three types of visual evidence, namely 3D printed models, 3D visualizations, and photos, to illustrate the case of a victim with a head injury. In all three evidence formats, the skull of the victim was presented. After assigning the visual evidence, ask each participant questions to assess their understanding of the case. The results show that the 3D printed model can best convey and explain the technical details of the case.

“Evidence presented in court cases needs to be clear so members of a jury can understand it,” explained Dr. David Errickson, a lecturer at Cranfield Forensic Institute. “There has been a rapid development of 3D printing in the last decade across industries such as manufacturing, healthcare and dentistry but there are very few examples of 3D printing being applied in forensic scenarios in the published literature. The documentation of crime scenes using a terrestrial laser scanner is not a new concept, but there is limited literature on the printing of these models. In order for 3D printing to be used in forensic science, particularly in courts of law, the discipline needs a recognisable evidence-base that underpins its reliability and applicability.”

One of the main advantages of 3D printed models comes largely from the tactility. The printed forensic model is based on an accurate 3D scan of physical evidence, which can be held and manipulated by jurors, allowing a higher degree of inspection.

As Rachael Carew, a researcher in the Department of Security and Crime Science at University College London who is also working on the project, said: The creation of physical 3D replicas allows for higher levels of interaction as users can hold, rotate, feel and inspect the object, something that is not possible with traditional 2D photographs or virtual 3D models. 3D replicas could also allow for the visual representation of evidence that otherwise would not be able to be presented in a court of law, such as human remains, and can be acquired from scanning techniques that are non-invasive and non-contact, helping to maintain the integrity of the original material.”

3D printing has other potential forensic applications both inside and outside the courtroom: it can be replicated for crime scene demonstrations in the courtroom, or it can be used by the police to reconstruct the elements of a car accident. The research team also pointed to museums, where 3D printing can be used to reconstruct and archive historical forensic materials.

In their recent research, the Cranfield team is improving the 3D printing technology to promote the use of the technology in the forensic environment and calling for further research on the broad potential of AM in the field of forensic medicine. As part of the ongoing research, the team is working with 3D scanning expert FARO Technologies UK.

“Within a very short time after a crime, urgent steps must be taken to avoid deterioration of the scene and loss of evidence,” added Marcus Rowe, Public Safety and Forensics Account Manager at FARO Technologies UK. “3D forensic documentation captures the entire scene before the site is compromised. With this digital evidence, forensic scientists can examine the scene at a later date for lines of sight, a bullet trajectory, or a blood spatter analysis. 3D scanning turns crime scene sketches into a digital forensic tool.”