Part of an ongoing series on how the 3D printing hype bubble has affected the lives of the individuals involved. To read the another story in this series, head here.

In the Age of Gold, historian H.W. Brands writes about how the American psyche changed after the famous Gold Rush of California, “The old American Dream … was the dream of the Puritans, of Benjamin Franklin’s ‘Poor Richard’… of men and women content to accumulate their modest fortunes a little at a time, year by year by year. The new dream was the dream of instant wealth, won in a twinkling by audacity and good luck. [This] golden dream … became a prominent part of the American psyche only after Sutter’s Mill.”

In the middle of the 19th Century, there wasn’t just one gold rush, but a series that occurred throughout the world, from the US all the way to Australia. When it was discovered that there was gold in the hills of California, the dream of striking it rich brought some 300,000 people from all over the globe to what would be nicknamed the Golden State. And, not long after, the discovery of gold in New South Wales and Victoria, would set off Australia’s own boom. There’d also be new gold mining industries erupting in New Zealand, Brazil, Canada, and South Africa.

Since the series of gold rushes that swept the globe left their mark on civilization, other large-scale trends have stirred the popular imagination with the dream of easy money. At the end of the last millennium, it was the dot-com boom, in which new internet companies drove the NASDAQ to a high of 5,132.52, as investors overlooked typical stock value indicators in favor of technological hype. Soon, the boom revealed itself as another economic bubble, in which some, like Amazon, survived and established themselves as key members in the industry and others, like pets.com, faded away.

Most recently, the desktop 3D printing revolution made a thirty-year-old technology catch the eye of the media and public at large by dramatically reducing the cost and increasing the accessibility of 3D printing. The resulting excitement led to amazing innovations, as well as overblown hype that saw some 3D printing stocks increase to four, five, and even ten times their current values. During that time, there were numerous analysts pointing out that the P/E ratios of these stocks were tremendously exaggerated, but investment continued.

3D printing stocks are now back down to more reasonable levels, but, in the storm that was the 3D printing hype of the past few years, there were huge technological breakthroughs, even life-saving medical procedures, as well as tremendous flops, scams, and lost life savings. As the public became aware of this exciting tool that could enable custom, personally-tailored products – ones that they could even design and manufacture themselves – brilliant start-ups were born, some existing companies became bigger, and still others have already been forgotten. Also in this hype, there were those who saw the opportunity for a quick buck, not unlike the gold rush.

The storm isn’t over, which means that we can learn from these existing stories, including those that involve failed get-rich-quick schemes, opportunistic hucksters, and devastated lives. One illustrative story that came out of that hype bubble one relayed by Jason Simpson, a business owner and Maker in Melbourne, Australia.

Before entering the world of 3D printing, Jason Simpson ran an engineering business. Over the course of twenty-two years building up Advanced Rollforming Technology, Jason had acquired a reasonably equipped engineering workshop, which included a lathe and milling machine and many other pieces of tooling and measuring equipment. His business enjoyed designing and building a wide range of items such as, equipment for manufacturers, radiation protection equipment, as well as more specialized machines to aid the manufacture of radiopharmaceuticals and imaging equipment, like X-Ray systems. For instance, ART built a micro-focus X-Ray system for the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) in the 90’s and, around 10 years later, built a large and very powerful phase contrast imaging micro-focus X-Ray system for the physics department at La-Trobe University. As a natural progression from his interest in imaging equipment and robotics, Jason was turned onto 3D printing.

A giant printer and the birth of 3D Group

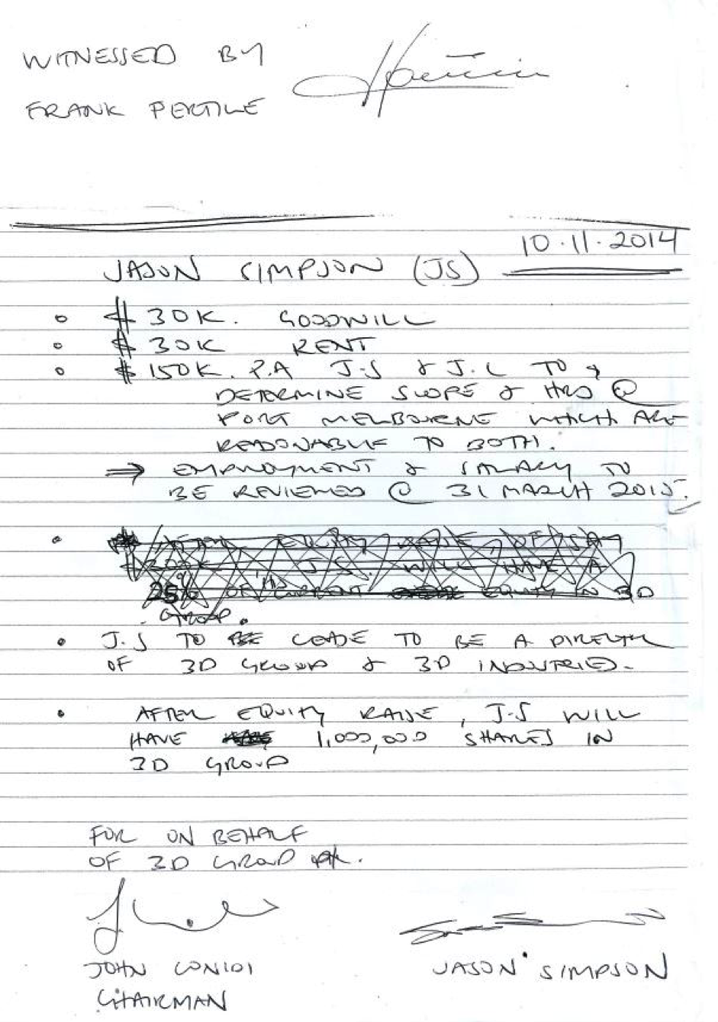

Jason believed that what the Australian (and global) markets would demand most would be a cost-effective, large-format extrusion 3D printer and, so, financed in part by his friend Dejan Popovski, Jason designed and constructed what may have been, more than a year ago, considered the largest extrusion 3D printer in the industry. Like many DIY-style 3D printers, this was a passion project, but with the enthusiasm for 3D printing circulating in the wind, it gained a lot of attention, particularly from two investors. According to Jason, John Conidi and Frank Pertile told him that they would launch his printer to success, get his newly founded ART 3D listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX), and, ultimately bring them all financial profit.

John Conidi had previously grown the largest medical imaging company in all of Victoria, Australia, Capitol Health. Not only that, but Bloomberg’s business profile describes him as having “over 14 years of experience in developing, acquiring and managing businesses in the healthcare industry with a focus on diagnostic imaging. His role in strategy, management and business development has driven the rapid expansion of Capitol, increasing its market capitalisation from $20 million to more than $500 million in 8 years.” Frank Pertile seemed equally impressive to Jason. Reuter’s profile lists Pertile as having “held positions with ASX-listed wealth management companies in both client-facing and head office operational roles.” As investors in Jason’s nascent 3D printing business, their impressive resumes lent enough confidence to easily envision ART 3D’s success.

The first step to making a successful company would be to incorporate the business. As Jason tells it, his new investors had impressed upon him that, to incorporate the business, it would be necessary to consolidate all of his manufacturing equipment, and the IP for his large-scale 3D printer, under one company. By March, 2014, ART3D had gone from a small, two-person operation to the foundation for a potentially ASX-listed company called 3D Group, Ltd.

In the beginning, 3D Group had one initial offering, Jason’s original Sabertooth 3D printer, which had a build volume of 1000mm x 1000mm x 400mm, or 3.3’ x 3.3’ x 1.3’. But, as Inside , the biggest conference related to the tech, was to hit Melbourne in July, 2014, Jason tells me that Conidi and Pertile asked him if he could build a bigger, better printer for the launch of 3D Group at the Melbourne show. Jason explains, “After a bit of resistance from me, they said, ‘The printer doesn’t have to be going at the show, as long as it’s complete and what we will eventually mass produce.’ I finally said ok, but we would need staff and some equipment.”

During the four months leading up to the event, Jason says he worked tirelessly on the machine and, in an effort to meet deadlines and deliver a working product, he requested funds from his investors to purchase supplies, hire employees, and so on. Jason says, however, that, oddly, Conidi and Pertile were reluctant to turn over any cash to a business they’d agreed to be a part of. So, when necessary, Jason, Dejan, and their new staff of four employees began dipping into their own pockets for things like materials, hardware and running costs, like power, phone, and internet.

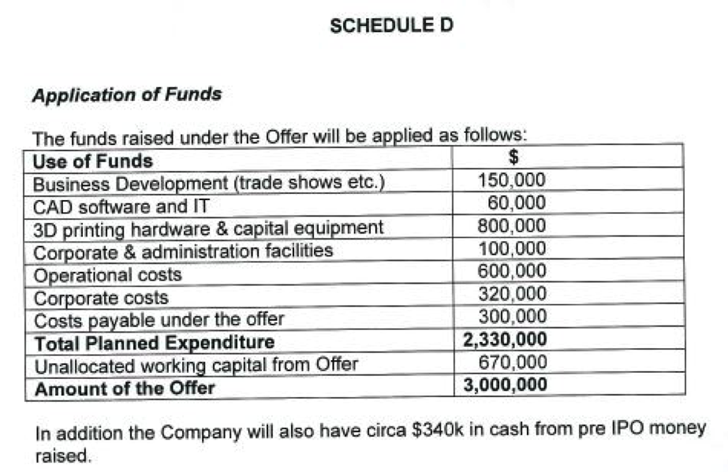

Jason explains, “One of the things that I really needed was a new PC because I was using an old laptop to do all of the designing. That took months for me to get a complete working PC. Invoices that I submitted just did not get paid.” He adds, “In our original [Heads of Agreement], I never saw money for the CAD programs or for the 3D printing hardware and capital equipment, that we had first agreed on and budgeted for [listed below], apart from the essential components that were needed for the printers we were building at the time. Frank did buy a 3D printer and a scanner (that I never saw). And we did build a printer, but that’s all I saw.”

Three printers, rapid expansion

From the beginning, 3D Group had always had plans of breaking into the 3D medical sector, according to Jason. The launch of 3D Group spin-off 3D Medical, then, makes sense, given Conidi’s Capitol Health’s own medical imaging services. The ability to convert CT and MRI scans into 3D printable models requires knowledge, skill, and software, but is well within the realm of possibility, even the next logical step, for a company such as Capitol Health and patient-specific, printable models could serve to help doctors prepare surgeries or teach med students. The plan, Jason says, was that 3D Medical would provide Capitol Health will all of its 3D scanning and modeling services, while 3D Group would provide 3D printing to 3D Medical.

Additionally, 3D Group began to make deals with other businesses. Two Memoranda of Understanding had been signed between 3D Group and a company called Bastion EBA that would see 3D Group 3D printing for the company, with licensing agreements that could lead to 3D printing models of athletes famous in the Australian sports world.

By the time Inside rolled around, Jason and his crew had managed to build the Mammoth, their second generation, large-scale 3D printer. “We fitted the last component as the much-delayed truck came to pick it up for the show. It was not working, but it was complete.” Jason adds that only two of the four additional staff employed to build the Mammoth were kept on after the show, “[Frank and John] said they would employ workers #3 and #4, but it soon became clear that they were not going to. Money seemed to always be an issue.”

Regardless of internal dynamics, the printer was well received at Inside . “The new Mammoth 3D printer, that could print a max area of 50 inches square, was a hit. I argued that the cost of this printer should be at just over $AU100,000. Frank Pertile decided to price the Mammoth at AU$80,000.” The attendees at the event were indeed impressed at the sheer scale of the thing. At over six-feet tall, it towered over most full-grown adults there. And, as a result of the startup’s huge splash at Inside , 3D Group was reported on in a long list of publications.

As the attention towards 3D Group increased, so did the startup’s business plans, according to Jason. He says that Conidi and Pertile were no longer focused on large-format printers. Instead, small, user-friendly machines was where they were heading. Jason claims that he protested that the market was already over-saturated with such printers, that 3D Group could stand out with the Mammoth. But the Australian government, like national governments the world over, was interested in education, getting a 3D printer into every classroom. Jason admits that, early on, “John did mention that he had a plan to get a 3D printer into every school, if not every classroom, at the expense of the taxpayer, very early in my meeting him.” So, that’s where they thought they’d get their funds next.

Referring to an October 13, 2014 announcement by the Victorian government to supply about 400 schools in the state with desktop printers, the company put out an October 14 press release (PDF) that read, “3DG has designed and manufactured locally the world’s first ‘School Printer’ – specially designed to meet the rigorous requirements of an education environment, without the price tag. The School Printer will have dimensions 990mm x 580mm x 580mm and dual extruders providing maximum functionality, speed and performance,” before going on to describe a complete platform, including specialty educational software.

Jason says of their efforts to build a school-specific 3D printer, “They told us for a long time that they were in with the government (of the day) and they had the contacts to get our printers in schools. There was an election coming up and we had to design a printer for schools we were told. They would get the government’s media people out to film our printer and use in in election campaigning. When it came to the final weeks before the election, it was leaked to me that Conidi and Pertile had been talking with Airwolf and had planned on buying Airwolf printers to fill the possible government orders. My team and I had just designed a cheap printer that could print 1000mm x 600mm x 500mmH model and could be built for under $10,000 if we had the volume.” The plan to get the Airwolf printers before the election never came to pass, but it has been confirmed by Airwolf that the Australian company is now an authorized reseller, though the resale of Airwolf 3D printers is in a very preliminary stage.

While at Inside , Jason tells me that he also overheard Frank Pertile speaking with 3D printing stock analyst Gary Anderson about a different venture that Jason had not been previously made privy to. 3D Group had, apparently, partnered with West Australian mining company Kibaran Resources to form a new corporate entity named 3D Graphtech. Using minerals excavated from Kibaran’s Epanko graphite fields in Tanzania, the new firm would work to develop a form of 3D printable graphene. 3D Graphtech had even managed to enter into a research agreement with CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation), the Australian government’s scientific research arm, towards this end.

Jason adds, “I also overheard Frank Pertile tell Gary Anderson that 3D Group may do a reverse takeover or back door listing to get on the ASX.”

From beer to mining to 3D printing

From beer to mining to 3D printing

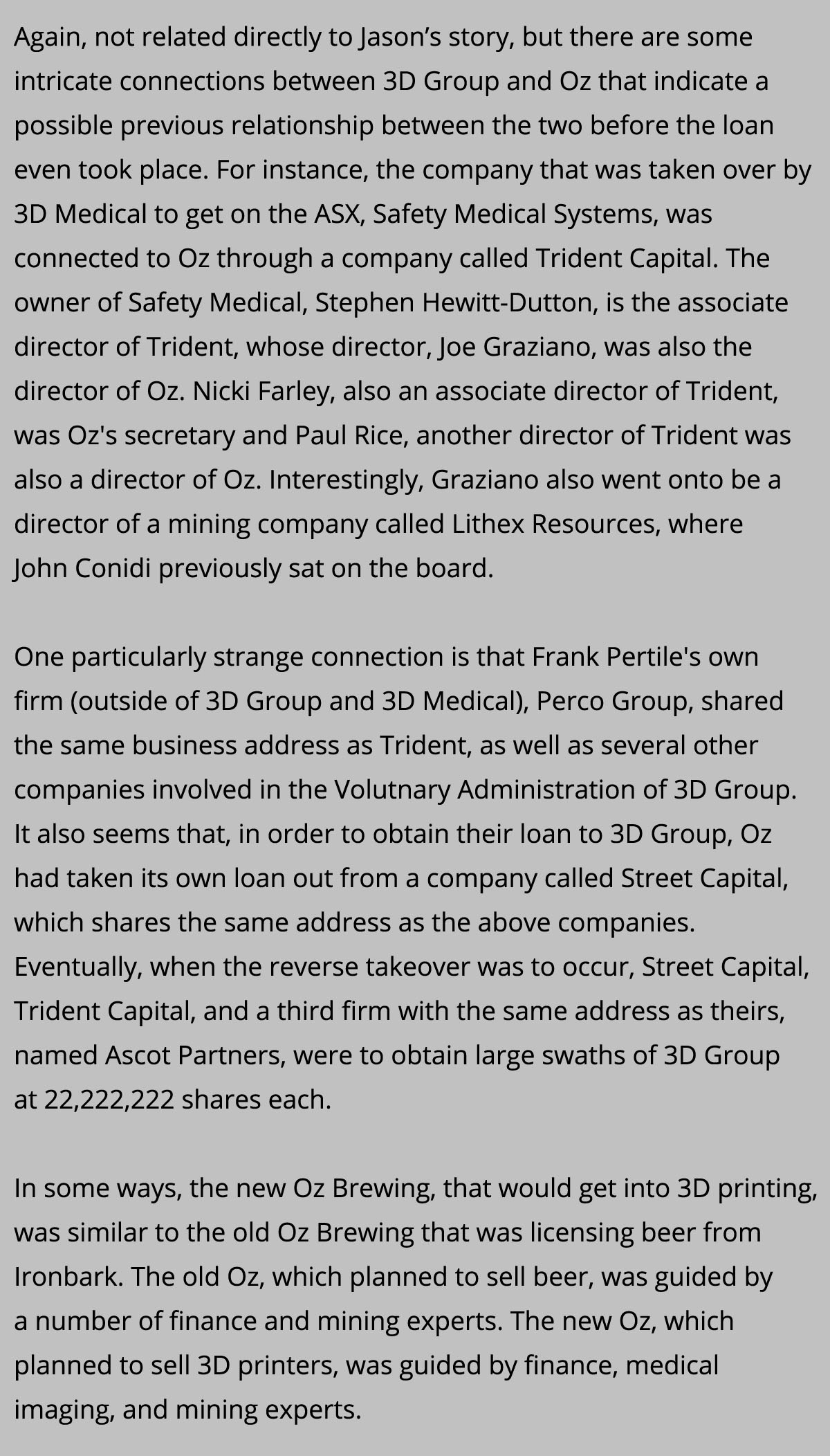

When a company without sufficient funds wants to get listed on a stock exchange, they can sometimes find another company that is already publicly traded, but no longer conducting business or has much value, and perform what is called a reverse takeover. Eventually, on February 6, 2015, 3D Medical would use this tactic to get listed on the ASX, via a takeover of penny stock Safety Medical Systems. 3D Group’s own plan to get listed would involve a firm called Oz Brewing Company, a previously listed company that was once in the business of selling beer.

Jason couldn’t quite understand why, but, before the takeover was to be initiated, he says Oz had loaned 3D Group a sum of approximately $430,000. As Jason says he was never given the loan agreement, he says he has been trying to determine the purpose of the loan ever since. Jason’s father suggested to him that this loan was meant to demonstrate that Oz was serious about the reverse merger.

From the seven months between March and October of last year, other than the three 3D printers built by Jason and his team, 3D Group had yet to release a single product. But they had managed to create three separate businesses, two of which were publicly traded. They also had a $430k loan to Oz that needed to be repaid.

Things turn sour

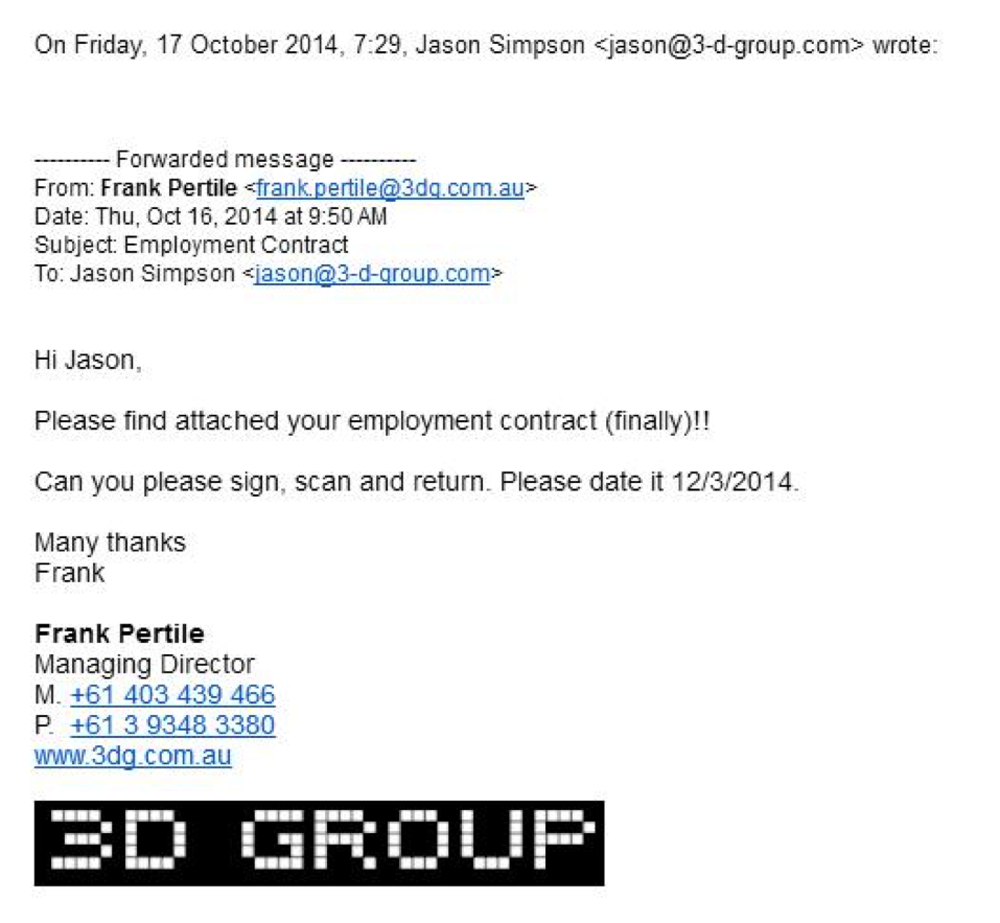

Then, in October, Jason says that Frank asked him to sign a back-dated work contract, that he says was a re-negotiation of his position. He explains, “On the 16th of October, 2014, I was asked to move up the date of a work contract as part of the due-diligence process. The work contract was effectively a re-negotiation of our Heads of Agreements and Memorandum of Understanding. I was also told it was a requirement of the ASX. When I told them that there is no way I was going to sign it, the relationships turned sour from that point on.”

Jason continues, “[I sat through] 6 hours of 3-against-1 finger pointing that all the company’s problems were somehow my fault and, during that time, they pointed out that my workers and Dejan Popovski would most likely lose their houses they had regular repayments to make. I was also told that I would end up with a huge bill from the tax department if the company was placed into administration [or Chapter 11 bankruptcy, in US terms].”

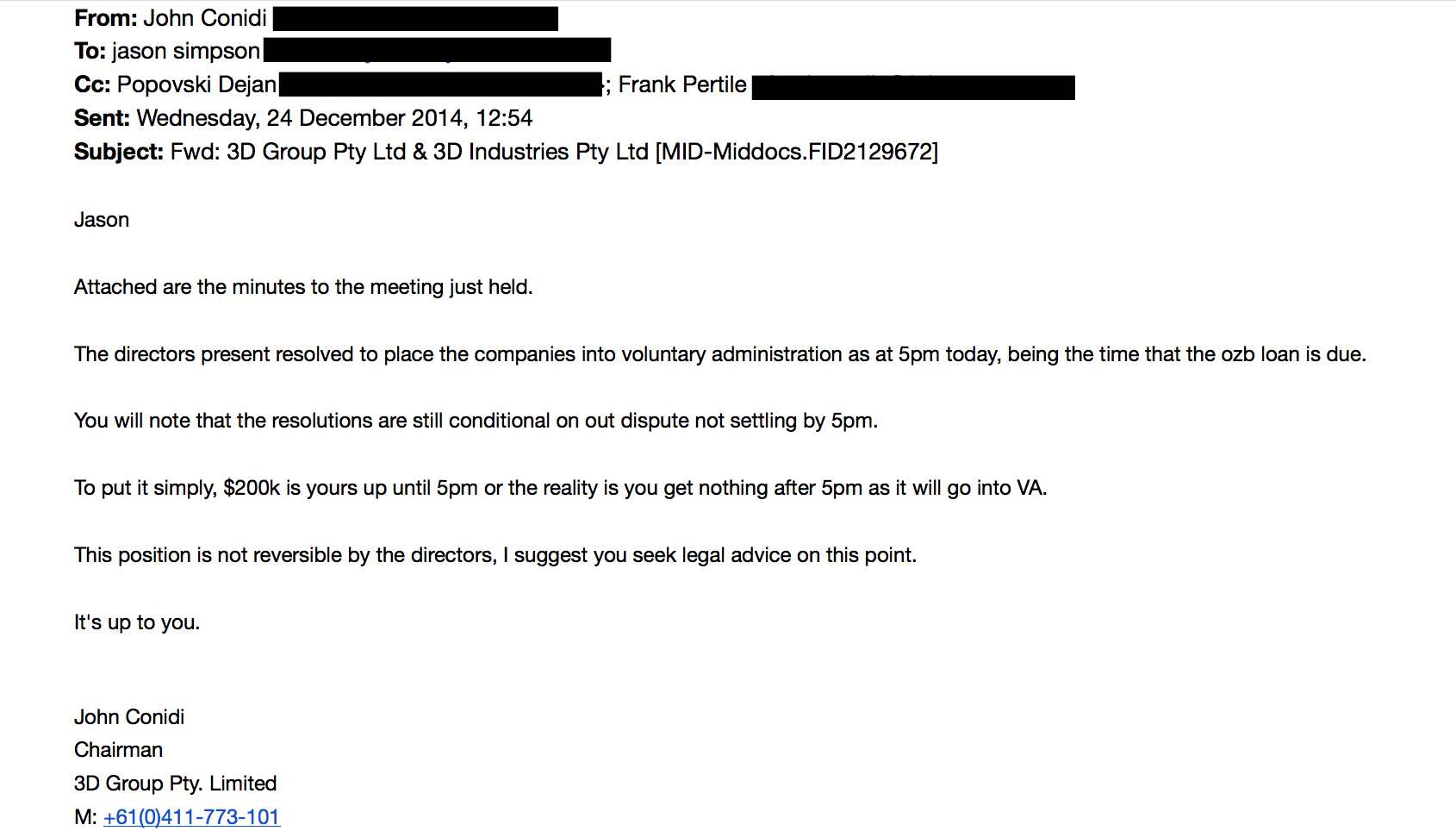

In an email exchange, in which Conidi sends Jason the minutes of the meeting, Conidi writes, “To put it simply, $200k is yours up until 5pm or the reality is you get nothing after 5pm as it will go into VA. This position is not reversible by the directors, I suggest you seek legal advice on this point. It’s up to you.”

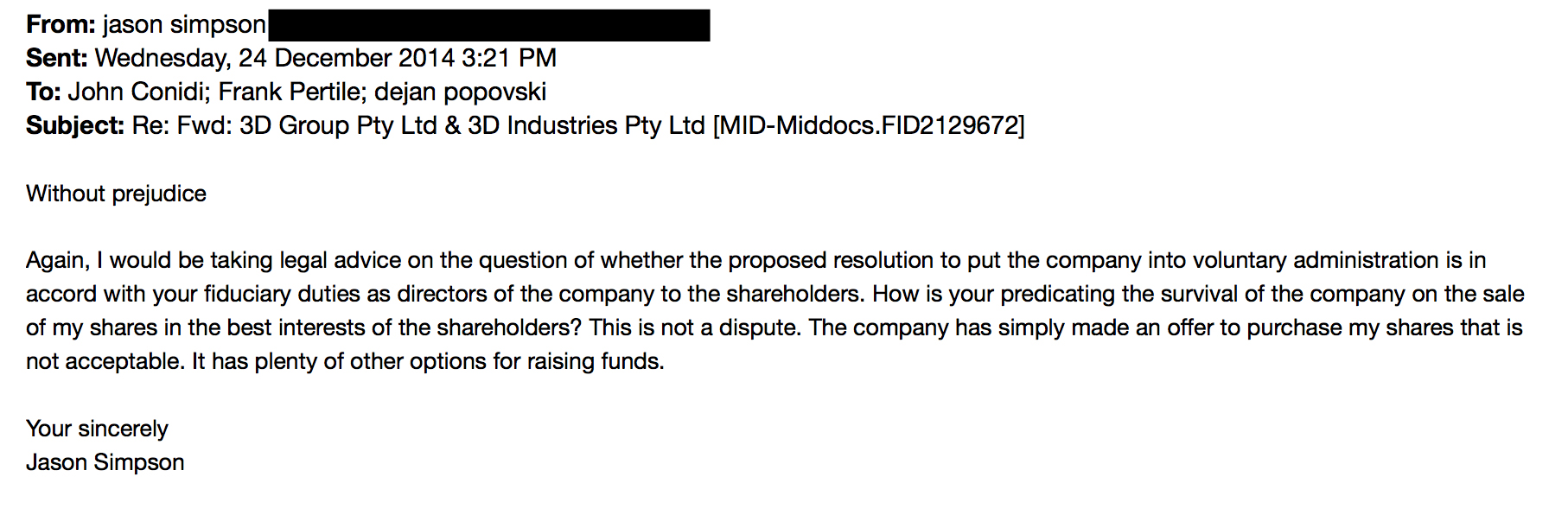

Jason responds by writing, “How is your predicating the survival of the company on the sale of my shares in the best interests of the shareholders? This is not a dispute. The company has simply made an offer to purchase my shares that is not acceptable. It has plenty of other options for raising funds, and it is unconscionable to suggest that my acceptance of a bad offer is the only way for the company to move forward.”

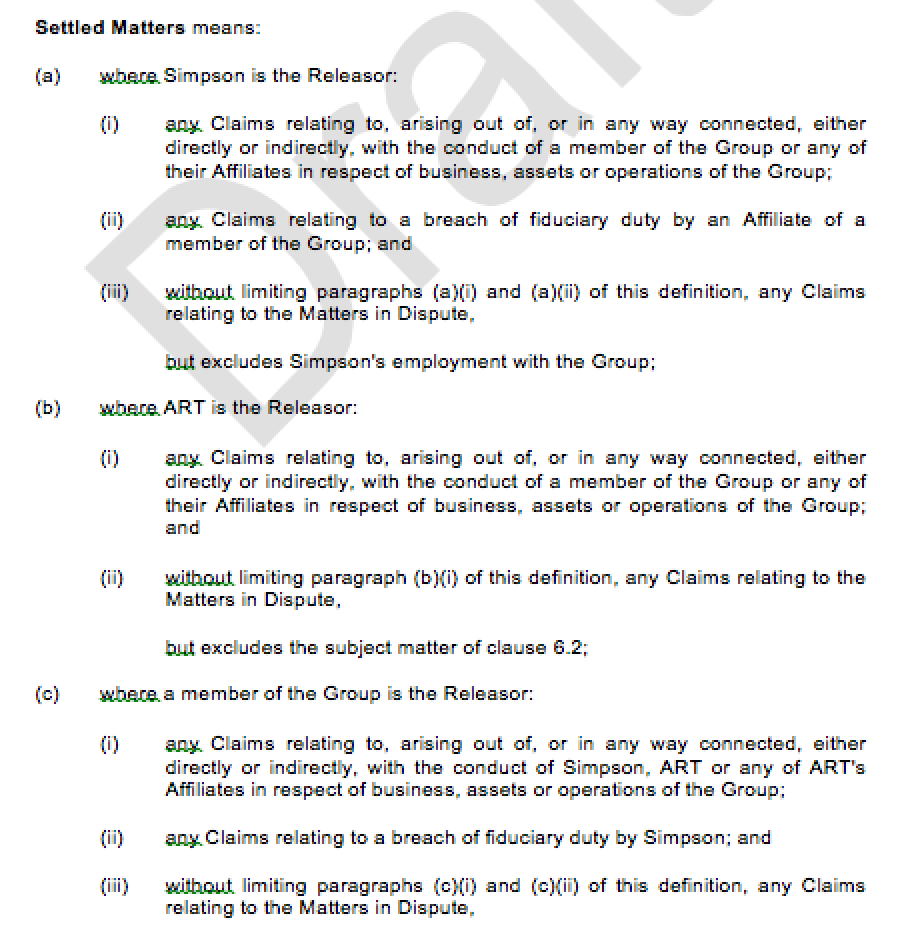

Voluntarily Placed into Voluntary Administration

OZB then announced via the ASX, before the Close Of Business on the 16th of Jan, that 333D Pty Ltd. had entered into a Deed of Company Arrangement with the third party administrator, Mackay Goodwin. Jason tells me that the agreement effectively saw a new deal in which the loan was extended, but that the only difference made in the corporate structure was that Jason would lose all of his shares and his position on the board. Additionally, all of the assets of 3D Group were to be transferred to 333D, Ltd.

The Status of 333D Pty Ltd.

I reached out to Frank Pertile and John Conidi to understand, from their perspective, what had taken place to cause 3D Group to go into VA, with Frank responding, “The reality is simply that we had a founding director take the decision that he wished to exit the Company and despite a number of attempts an acceptable fair, reasonable and commercial financial settlement for his exit was not able to be reached. This triggered a series of events the culminated in 3D Group being placed into voluntary administration and it subsequently being acquired from the Company’s Administrator by 333D…”

When I probed further, referring to Jason’s side of the story, Frank elaborated:

It is inappropriate for us to participate in a ‘he said – she said’ scenario with you. It’s in no one’s interests to do that and is simply something we will not do.

I will say this for your benefit Michael. Jason has clearly formed and communicated to you a version of history that is complementary to his position and one designed to get a reaction from the other Directors. The truth is something quite different to what he appears to be putting to you.

The Directors of 3D Group acted in accordance with their commercial and legal requirements as Company Directors and there is really nothing further to add.

In his previous email, before I had probed further, Frank tells me that the company is moving forward, without Jason, as 333D, or T3D as they refer to it, saying that they continue to develop large scale printers, “To this ends we have designed 3 new models and have just completed the prototype for our 843 (so called as it’s print build area is 80cm x 40cm x 30cm). We continue to receive interest in our custom printer design and build service and are working with several customers on this front. Our service bureau work is steadily growing even though we have not commenced marketing in earnest.”

Frank also commented on a distribution agreement with CreoPop, the makers of the successfully crowdfunded 3D printing pen, which relies on UV curing liquid resin instead of heating plastic to draw 3D shapes. “We have, as you’ve noted, executed a Letter of Intent with CreoPop to distribute the product in Australia and New Zealand and we are discussing a potential R&D collaboration around utilising the CreoPop photosensitive resins in large format industrial printers,” which was confirmed by CreoPop founder. “The company is also working with desktop 3D printer manufacturer Airwolf 3D,” Frank says, “Additionally, we have secured a distribution agreement with Airwolf 3d for Australia and New Zealand and continue to negotiate with several other companies for similar agreements.”

As for 3D Graphtech, the details were not extensive, “The work around graphene and the use of graphite in 3d printing remains an area of interest for T3d via it’s acquisition of 3D Group and it’s subsidiary 3D Graphtech Industries. The development of new printing materials is an area we monitor closely and particularly around the use of graphene which we believe offers some very exciting possibilities.”

Though I never heard a response from Kibaran Resources, the part owner of 3D Graphtech that recently brought John Conidi on as a director, I did get a response from CSIRO, the Australian research organization that funded 3D printable graphene research. Alex Kingsbury, the Group Leader of Additive Manufacturing Research at CSIRO’s new industrial 3D printing lab, wrote, “Sorry this was before my time… The research never went ahead, and the company that sponsored the work went into receivership, so this may well explain the lack of information!”

I had also asked for information about 3D Medical, but Frank, the CEO of 3D Medical, did not comment. The company does, however, have four confirmed distribution agreements with various medical tech groups. And, based on newsletters received by 3D Medical investors, the company continues to explore 3D printing. One investor received an email from the company that read: “Win a 3D Print Model…. Describe your patient’s anatomy and how a 3D printed model will improve their surgical outcome….. Click here to enter.” A fellow investor responded in a forum thread on the topic, “For a bonafide company within the medical sector I find the above mail out quite alarming. Surely they don’t have the resort to this sort of retail marketing. If they are trying to gain a reputation within the medical profession the latest marketing is surely a kick to the nuts.”

333D, 3D Medical, and 3D Graphtech are all continuing onward, but Jason, a once successful engineer, is struggling to do so. The reason, Jason tells me, is that 333D owns all of the assets from his previous engineering business, essentially all of his workshop equipment. Jason has contacted government agencies to investigate the companies. In the meantime, he’s sought unemployment assistance, with some luck. He and his wife received their first welfare check on May 19th.

Lessons on penny stocks, business contracts, and Voluntary Administration

I’d wondered if such an arrangement, assigning all of one’s assets to a company, was normal for setting up a business, as had occurred in Jason’s situation. So, I asked IP lawyer and 3D printing expert John Hornick. Without knowing which parties were involved, he told me that such an arrangement is not out of the ordinary:

I can tell you that it is common for investors to require individual inventors or product developers to assign their rights to the company that will commercialize the invention or product. If those rights are owned by the individual’s existing business, or if the investors believe that the business could own such rights, they might require the business to assign the rights to the commercializing company. In this situation, if the rights or assets assigned by the existing business to the commercializing company did not relate to the 3D printer, I don’t have any way of knowing why the investors would require that assignment, but they could have had good and legitimate reasons for doing so.

John Hornick couldn’t speak to the rest of the story, but, like Jason, I was confused as to why Oz Brewing would only agree to a loan extension if Jason were out. The formation of 333D, under the VA, had perplexed me, too. Looking into Voluntary Administration, I’d read that, in addition to salvaging businesses, the practice can sometimes be used for corporate restructuring.

Saul Fridman, a former Associate Law Professor with the University of West Sydney, explains in an essay on the topic (PDF), “Once the [bankruptcy] administrator is appointed, the powers of all officers of the company are suspended. Thereafter, officers of the company can only exercise their powers with the consent of the administrator… In extreme cases, where unscrupulous directors are concerned, what may result is the administrator acting as a puppet of the directors, while those same directors are seeking to take advantage of the statutory defences to insolvent trading referred to above (as well as taking advantage of the statutory moratorium against enforcement of personal guarantees they may have given).”

Referring to a court decision regarding VA, Intan Eow, Senior Associate at King & Wood Mallesons in New South Wales, explains (PDF) that the practice may be used to reorganize the company and redistribute shares, “Put metaphorically, it is an abuse if the debtor reorganises only to carve the pie up differently without enlarging or preserving the pie. As Judge Smith in Re Integrated Telecom Express Inc stated: ‘a [Chapter 11 bankruptcy] petition must do more than merely invoke some distributional mechanism in the Bankruptcy Code. It must seek to create or preserve some value that would otherwise be lost — not merely distributed to a different stakeholder — outside of bankruptcy.’”

The fact that all of the companies involved were related to the trade of penny stocks led me to wonder why a company like 3D Group, which hadn’t yet released a marketed product, would be looking to publicly trade so early on in its business. I was particularly interested, as I read that the Securities and Exchange Commission often warns that inactive microcap stocks are frequently used to initiate pump and dump schemes via a reverse merger. In these cases, a company performs a reverse merger to take over a publicly traded penny stock, inflates the shares, and then sells the shares through holding companies and consultants, so as not to alert the public to the directors’ sales of shares.

Catching articles on 3D printing penny stocks on Nanalyze, I contacted the tech finance site to see what they thought about 3D Group. Nanalyze agreed to write an article on the company for 3DPI in which they explore the company further. In it, they warn of the dangers of investing in penny stocks: “Oz Brewing currently has a market cap of $4.4 million USD and trades at .007 cents a share. Any stock that trades at a fraction of a penny should be immediately shunned by investors. At this price it would have been kicked off the major exchanges for not meeting minimum market cap requirements and then would be subject to the lax regulation of the [Over The Counter] market it will most likely begin trading on. 333D may instigate a reverse stock split in order to not appear so heavily diluted. Situations like this usually develop from companies that are issuing shares left and right to ‘consultants’ to keep the company running while subjecting the current shareholders to heavy dilution.”

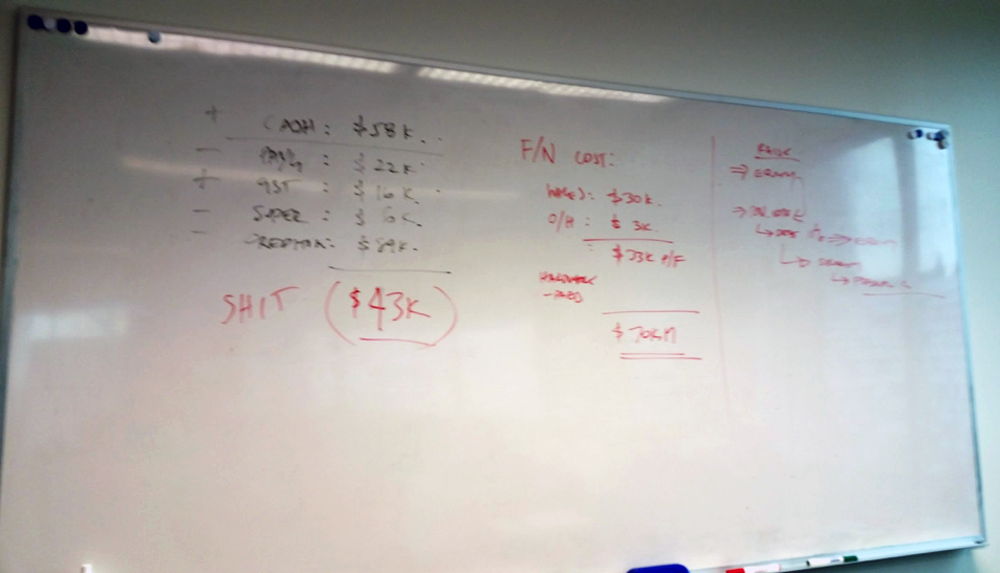

Interestingly, Jason tells me that he did see large bills for consultants, “December, I was finally given some details of the running of the company as well as the new address of the company. The accounts where totally shocking to me, $170k spent on consultants in October, November & December. $3k on a phone bill, when the bill was really less than $300. They even used the $33k rent they said they were going to pay me for our facility to make the accounts look how they wanted them to look.” He adds, “I also have a photo of the white board that John (with Frank’s help) put all of the figures onto at the meeting on 29/11/2014. It clearly shows John telling us there was only $53k in the bank, when the financials given to me later in December show that we had $248,533.00 in the bank at the time.”

As for the deal with CreoPop, Nanalyze writes, “While the CreoPop received a great deal of positive press, being able to ‘exclusively market and distribute Cre0Pops in Australia in New Zealand’ doesn’t sound like a promising future. What value add can I get from ordering a CreoPop pen through 333D when I can just order one direct from the company that makes them? How much is the maximum possible sales that can be achieved by selling a niche product to two countries with a total population size of 27 million? Is 333D’s business model to distribute other people’s 3D printing products?”

Life after the hype

During the VA process, the VA is first required to pay off any debts, before going on to conducting other business. One debt, according to Jason, was the rent on their original facility, containing Jason’s 20 years of equipment. Instead of paying that off, Jason says, they sent him a huge bill for that very equipment, “The admin continued to dangle the carrot of him going to pay my accrued employee entitlements, the storage and the bills owed to me by the companies pre-VA. Well last week, they sent me a letter rejecting my claims and sent me a 40k bill. The 40k bill relates to them claiming that I won’t give them the assets [manufacturing equipment] back. They say that the assets are worth 91k and they owed me 50k and that leaves me with a bill of 41k.

“Now, keep in mind that I am not the owner of the factory and that 3DG/3DI have not paid rent for 20 months. I have not been there since the owner told me to leave months ago. I had no other place to store the assets or any money to move them and because of all of the bills being not paid. I have also lost a lot of personal and company items that I was not able to move out of the factory. Very important point on this is the admin allowed [the other employees] Ray and Jarred to strip most of the parts off the 3d printers in January and, in late December, disabled the other equipment so I could not use it. I don’t know what they have done to each machine, but it makes it worthless to me.”

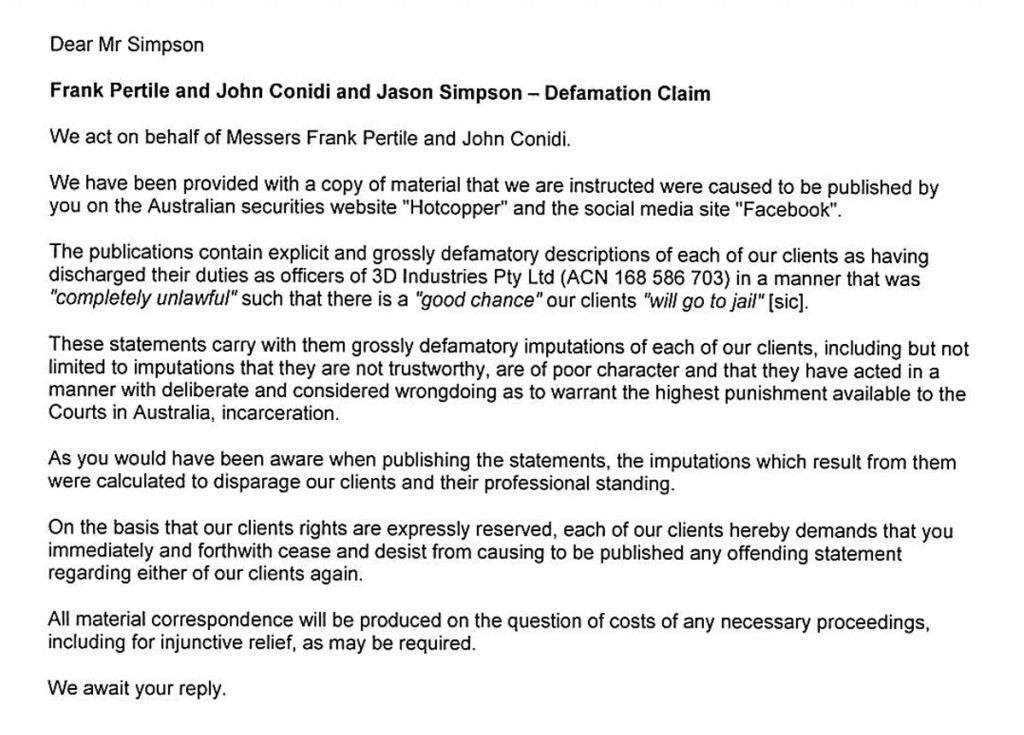

He also says they sent him bank accounts to demonstrate this loss, but accidentally sent him a more recent statement saying that the VA has already paid himself and other creditors, without paying the rent bills for the facility housing the equipment. Since then, a Defamation Claim was made against Jason by Conidi and Pertile. The letter reads:

We act on behalf of Messers Frank Pertile and John Conidi.

We have been provided with a copy of material that we are instructed were caused to be published by you on the Australian securities website “Hotcopper” and the social media site “Facebook”.

The publications contain explicit and grossly defamatory descriptions of each of our clients as having discharged their duties as officers of 3D Industries Pty Ltd (ACN 168 586 703) in a manner that was ‘completely unlawful’ such that there is a ‘good chance’ our clients ‘will go to jail’ [sic].

These statements carry with them grossly defamatory imputations of each of our clients, including but not limited to imputations that they are not trustworthy, are of poor character and that they have acted in a manner with deliberate and considered wrongdoing as to warrant the highest punishment available to the Courts of Australia, incarceration.

At this point, Jason tells me, he has still been unable to find work, as 3D Group took control over his equipment, built up over twenty years. Without it he can’t return to his former engineering services, seeking him to attempt to reclaim the property from his roll forming business. To do so, he is having his investors’ business practices investigated by the appropriate government bodies. In fact, he heard from the Fair Work Commission, which is investigating the VA process and the Commission plans to hear his case. Jason also hopes to take his former investors to court and sue them for the rights to his property in order to re-establish his old business.

Having lost his business, Jason doesn’t have the roughly $50k to pay his legal fees and, for that reason, he plans on launching a crowdfunding campaign. $50k isn’t a lot for a crowdfunding campaign, particularly when you consider that the Form1 3D printer earned almost $3 million on Kickstarter, the 3Doodler reaped more than $1 million twice on the crowdfunding site, and the CreoPop pen earned over $200k on Indiegogo. If the 3D printing hype bubble could build up cash that high to launch some companies into success, it would seem fitting that the 3D printing world might be able to help someone for whom the hype bubble was much less fortunate.

In the gold rushes of the 19th century, there were hucksters selling Fool’s Gold, deceiving those looking to get rich quick with replicas of the real thing. The same has been true of all of the gold rushes that have followed. And, in an industry whose technology is heavily focused on reproduction, the deception of 3D printing hype is that much more tangible. There will be more hype bubbles and those looking to exploit them in the near future – marijuana, wearables, VR/AR – what we can learn during the current 3D printing boom and stories told by folks like Jason might prevent the negative effects from future gold rushes from being so extreme.

At the same time, because the 3D printing industry is still so new, there is still the potential to right wrongs, for lives to be repaired, and for those looking for help to get it.

Leave A Comment