Egypt captures the imagination like no other place on earth, rich in ancient treasures and tantalizing mysteries. The tombs of the golden-faced pharaohs preserved for eternity with their impassive stares, and the carefully painted treasure troves and painstakingly created models designed to follow them into the afterlife offer a rich snapshot of the deeply sunken past. No other culture in the world has held such an obsession with immortality combined with the profound power necessary to translate that desire into reality.

Of the tombs in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, that belonging to Seti I was widely acknowledged to be the most opulent and lavishly decorated. Seti I was pharaoh during the first half of the 13th century BCE; though the dates aren’t completely clear, generally his reign is thought to have run from 1294 or 1290 to 1274. After his burial, it was not until 1817 that his tomb was officially discovered by Giovanni Battist Belzoni; however, it had been looted previously and his body was not actually discovered until 1881.

The tomb was highly influential during the time directly following its creation; according to Egyptologists Nicholas Reeves and Richard H. Wilkinson the style of the tomb was “followed fully or in part by every succeeding tomb through the rest of the valley’s history.” Tutankhamun’s tomb has garnered a great deal more attention because of its intact state, but Seti I’s tomb has always been the jewel in the eye of Adam Lowe, founder of the Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation and the man whose pet project has been to scan the tomb and give it a new accessibility in the form of a 3D printed replica.

Recording Of The Tomb Of Seti I from factum-arte on Vimeo.

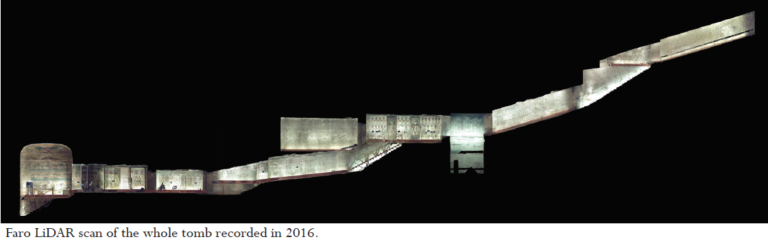

Despite the fact that Seti’s tomb is Lowe’s first love, even for him it was overshadowed for a time by that of Tutankhamun. In 2001, when Lowe first began to plan for the scan of Seti’s tomb he was, for a time, diverted into the project of scanning Tutankhamun’s. Only in 2016 was he able to devote his attentions to Seti’s resting place and the completed scans of two of the complex’s rooms are now on display in Basel’s Antikenmuseum. Every square inch of the two rooms presented at the museum was 3D scanned using the FARO Focus 3DX 130 laser scanner and the Lucida Laser Scanner. The Lucida scanner was, in fact, developed specially for this project by Manuel Franquelo and is capable of scanning a 48 x 48 cm area in one hour. While the resolution of the Lucida scanner is breathtaking, the data gathered is not compatible with that gathered by the FARO and required the development of a special protocol in order to create a holistic 3D digital replica.

This data, combined with use of advanced photogrammetry technology that allowed the team to pull information from photos, has made possible the creation of the most detailed and accurate replica of the space to date. And all without doing any damage to the rooms themselves. Previous efforts to duplicate the spaces, such as that undertaken by Belzoni himself through the creation of squeeze casts, caused stained or removed paint from the surfaces that they were designed to copy.

The hyperrealist detail in the scans means that it can be hard to distinguish between the real and virtual, and the realization of this potential is changing the approach to museumology and the very acts of collecting around the world. In fact, it is possible to enjoy the virtual replica even if you cannot travel to Basel itself, meaning that this kind of scanning and replication opens up access to sites to anyone who has an internet connection. The next step for Lowe and the Factum Foundation is to continue scanning, beginning with the crypt, the tomb’s next largest chamber. For this, they will utilize a team of ten local Egyptologists and Lowe hopes to raise €10 million (approximately $11.6 million USD) to fund the efforts. The first member of the team, Egyptian Egyptologist Aliaa Ismail, has already trained two of her colleagues in using the scanning technology.

Egyptologists, or simply Egypt fanatics, have been looting and plundering their way in, around, and through Egypt’s ancient treasures and dispersing them in collections and museums around the world. Not only does this mean that there are few sites in which the intact programs can be studied in situ, but it also has led to the loss or destruction of many objects. After Seti I’s tomb was opened, large chunks of the tomb and many of its contents were cut out and hauled away by trophy hunters. It is as a result of this that the Louvre and the British Museum, to name just two among many, have pieces of this tomb (and many others) in their collections. In the intervening centuries, the site has continued to be damaged by pollution, graffiti, and the reckless fingers of visitors. As Lowe noted in a detailed analysis of the process of the recreation:

“The reintegration of original elements or the mix of original facsimile elements is a complex subject. But the potential of facsimile reconstructions is again attracting public interest as it did in the second half of the nineteenth [century] when the cast courts opened at the V&A. The regeneration of damaged and dispersed objects assists understanding without putting the original object at risk. It focuses attention and results in a deeper appreciation both of the object and the reasons it looks as it does today.”

In addition to being available for viewing as if through a portal in space, these 3D technologies also allow for incredibly detailed reproductions of how the rooms were before the years of vandalism and decay left their mark. This digital restoration allows for the testing of a variety of theories both about the space and the impacts of various interventions by looters, the environment, or under current guardianship.This ability to bring the past across both space and time makes 3D tech an incredibly useful tool in the study and preservation of ancient sites and objects. Creating such a detailed record of the current state of a site also allows for monitoring its continuing state of decay and degradation, providing helpful information in its preservation.

Reassembling the tombs would require enormously complex and delicate negotiations with museums, governments, and individuals the world over and many are loathe to give up their pieces of this decidedly popular history. Conversations and outright arguments about repatriation of something as large as a tomb are not viewed with a great deal of optimism. However, with Lowe’s scan, the Hall of Beauties and the Pillared Room can make their way around the world without so much as a scratch, meaning that while damage has been done, there are at least possibilities to disincentivize the wholesale robbery that has previously been the norm.

The recognition of the potential that these 3D technologies have for the transportation of distant wonders to all four corners of the world is ushering in a new era of both shared information and respect for physical possession. This is just the beginning of the creation of databases that will allow scholars and aficionados access on an unprecedented level to all of the glories of the shared history of humanity.

For a detailed description of both the state of the tomb and the process of its documentation and replication, Factum has released a 40-page booklet on their website.