You’re probably reading this on a computer. Thank a machinist. Without precision machine tools and the people who operate them, your computer, desk, office chair, the cars in the parking lot, and the building around you wouldn’t exist. In fact, machining makes every aspect of modern life possible, from the food in your refrigerator to the clothes on your back. It has been that way since the discovery and subsequent refinement of metals such as copper and iron.

Granted, machining is a subset of the much broader manufacturing industry, but it’s important to recognize that sheet metal fabricating, injection molding, casting, semiconductor fabrication, and all the rest would never have developed without machined parts.

Even that new kid on the manufacturing block, 3D printing, relies on and indeed owes its very existence to machining, despite the fact that additive manufacturing is changing the way we design and build many products. Long story short, machining is here to stay, and it gets a little bit better, faster, and more accurate every day.

Touring the Machine Shop

These technology-enabled manufacturers are dramatically different from traditional machine shops that are more labor-intensive and still rely on manual machine tools. Digital manufacturers like FacFox are embracing automation like never before. For example, FacFox has developed proprietary technology that turns CAD models into machined parts and products in as fast as one day, and a large-scale capacity of hundreds of mills and lathes, which ensures that parts are shipped rapidly, on-time, and on-budget.

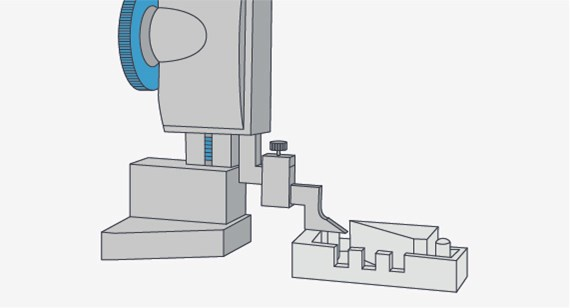

Now, let’s quickly look at precision machine tools, how machining really works, and what this has to do with part design. There isn’t space to cover the complete history of machine tools, nor to delve into saws, grinders, electrical discharge machining (EDM), and other ancillary equipment, but one key aspect any part designer should know is that most metal-cutting machines (they also cut plastic, by the way) can be roughly classified as either mill or lathe.

A great deal of technology lies behind each, but in a nutshell, a lathe grips a workpiece in a chuck and rotates it against a cutting tool, whereas a mill is an exact opposite, driving a rotating cutting tool against a workpiece that’s been clamped in a vise or fixture.

| THE DEATH OF MACHINING? HARDLY |

|---|

| While 3D printing seems to be grabbing most of the headlines in the manufacturing sector, CNC machining has confirmed itself as a permanent fixture. According to the Association for Manufacturing Technology, U.S. manufacturing technology orders continued a double-digit percentage, month-after-month, rise with machine tool orders totaling $2.13 billion, up 26 percent compared to the same five-month period in 2017. |

Another key item worth mentioning is that, while manually operated, hand-cranked machine tools are still in use, the majority of them today are computer-numeric controlled, or CNC, like at FacFox. As mentioned, most of what you read in the following pages will pertain to the latter.

Despite their fundamental differences, CNC mills—more commonly known as machining centers—and CNC lathes (turning machines) share many similarities. All have multiple axis points of motion, with which to drive cutting tools around and through the workpiece, thus removing material. All use drills or end mills to make holes, but where lathes are equipped with groovers, threaders, and other turning tools, machining centers use face mills, slotting cutters, and other rotating tools.

For many years, the standard lineup in any machine shop consisted of two-axis CNC lathes and three-axis machining centers. Some were horizontal, others vertical, but for the most part, work has bounced between the two until all machining steps were completed. Thanks to some clever machine tool builders, though, this line between lathe and mill has grown quite fuzzy of late. So-called multitasking machines combine a milling spindle and toolchanger with a lathe-style head and turret (the part that holds the tools). Similarly, mill-turn lathes combine both rotating and stationary cutting tools, while machining centers with turning capability have become increasingly common. FacFox, for example, use lathes with live tooling to accommodate features like axial and radial holes, flats, grooves, and slots.

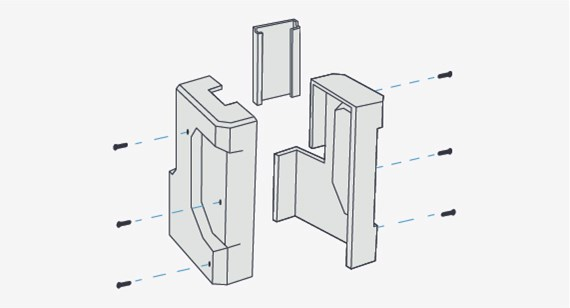

Machining centers may also have more than three axes. A five-axis mill, for example, can move all of its axes simultaneously, an attribute that’s useful for producing parts like impellers and hip implants. And a traditional three-axis machining center might be equipped with a head that tilts and/or rotates. This 3+2 capability is perfect for machining multiple sides of a workpiece in a single handling. Whatever the exact configuration—and there are many—each style of machine tool is designed to reduce machining operations and increase production flexibility.

Optimizing Part Design for Machining

If you’re someone who designs parts for a living, you might be wondering: Who cares? As long as I get my parts on time, and at a reasonable price, it doesn’t matter to me how they’re made, right? Well, not necessarily. Just as you need to have a basic understanding of how a motor vehicle works to arrive safely at your destination, a reasonable grasp of machine tool technology is necessary to any parts designer. This knowledge is especially important when working with a digital parts supplier such as FacFox, which can drastically accelerate the machining process—and often reduce costs—if certain design guidelines are followed.

The primer just offered is a good starting point, but the best advice short of actually programming and operating a machine tool for a few years is to work closely with your machined parts supplier. Ask questions, in particular ones like: “How can I make my parts easier to machine?” With that in mind, here are some key considerations when exploring ways to optimize part design for machining:

Keep it Simple

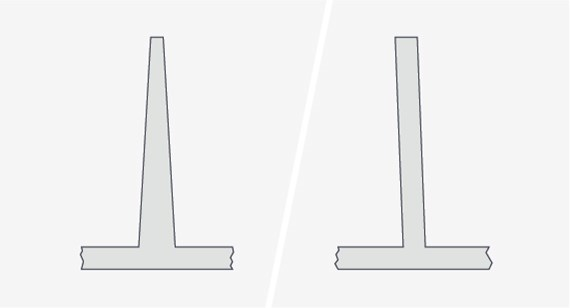

One of the most common mistakes even experienced design engineers and product developers make is to overly complicate their part designs. Consider breaking up single-piece, multi-faceted “super parts” into simpler components that can be bolted, glued, or screwed together. Unless required for functionality, avoid swept surfaces, as these generally require lengthy, more costly machining with a ball-nose milling cutter. Design parts with features that can be cut from one side wherever possible. This avoids multiple operations and possibly special fixturing, as well as having to use a more expensive five-axis machining center, or one with tilt-rotary (3+2) capabilities.

Consider Part Tolerances—When Necessary

Making parts more accurate than is absolutely necessary is another common mistake. When tolerances are tighter than needed, the machinist may be forced to modify the part program, use a special cutter, or even perform a secondary operation to meet that tolerance. Whenever possible, it’s better to stick with the default “block tolerances” called out on any part drawing, or ask your machining partner for advice as to what’s reasonable.

Stop Texting

Machined text looks really cool. It’s great for permanently marking parts with numbers, descriptions, and company logos. The problem is, it’s fairly expensive to produce. Each character must be traced with a tiny cutter, consuming valuable machine time. And don’t even think about raised text, as this means milling away everything that doesn’t look like a letter or number. Better options do exist, including laser marking or even a rubber ink stamp.

Use Caution with Tall Walls and Narrow Pockets

Cutting tools are made of hard, rigid materials such as tungsten carbide and high-speed steel (HSS). Despite this, they do deflect ever so slightly when subjected to machining forces, a phenomenon that becomes increasingly troublesome the farther out the tool protrudes from the tool holder—depending on the operation, carbide cutters are good to a “stick out” of roughly four times the tool diameter, maybe a bit more on soft materials, while HSS tools become problematic at about half that distance. This leads to chatter (an ugly rippled surface), difficulty meeting part tolerances, and poor tool life. The lesson for a designer? Watch out for deep, narrow pockets, or part features situated alongside tall walls, lest cutter deflection creates problems for those doing the machining.

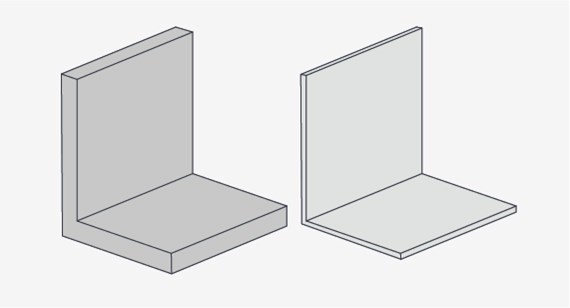

Use Caution with Thin-Walled Parts, Too

Similarly, thin-walled parts are also subject to deflection, but because most workpiece materials are nowhere near as rigid as the cutting tools used to machine them, the rules are a bit more stringent. Again, it depends on the part feature and material, but a good rule of thumb is to design walls that are no more than two times the thickness deep, and understand that any wall thinner than around 1/32-inch or so will likely cause problems. As always, check with your machining expert for advice.

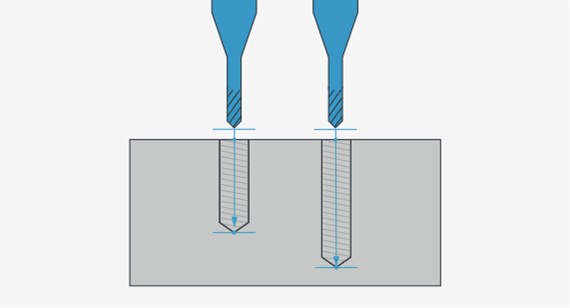

Drilling Deep Can Be Tricky

Holemaking is the most commonly performed of all machining operations. It’s most often done with drill bits that are a little different than the ones you find in any hardware store. As holes get deeper (say five to six times the drill diameter) evacuating the metal “chips” formed during any machining operation becomes increasingly challenging. If your product design requires deep holes, so be it, just know that the deeper they are in relation to their diameter, the more expensive the part or parts will be.

Navigating Sharp Corners

In machining, corners can be tricky, too. Say you’re designing an electronics housing for a product. On one side of the part, you need a pocket, inside of which will sit a 2-inch square circuit board. Someone unfamiliar with machining practices might design a square-cornered pocket, one just slightly larger than the board itself so as to provide clearance. Not a good idea. Those square corners will cost you dearly, as the only way to generate them is to burn them out with EDM, a machining process common in the injection molding and tool and die industries. Space permitting, consider oversizing the pocket so that an end mill can be used instead—in this example, a 1/2-inch tool might be appropriate, which means adding half its diameter (1/4-inch) on all sides of the circuit board, plus whatever additional clearance is needed to fit the circuit board. Another option is to cut reliefs or “dog ears” at all four corners. This might give the pocket a cloverleaf or T-shaped appearance but will make machining much easier.

There’s plenty more to think about. Just as deep pockets are a no-no with milled parts, overly deep grooves can be challenging to turn, and long, slender shafts can be tricky, too. Breaking the edges on turned parts with a radius or chamfer is no big deal, but requires an extra machining step on ones that are milled. And since we’re on the subject, be sure to ask your machining provider about its preferred method for deburring parts—some use abrasive wheels, while others “tumble” parts in small rocks, or blast them with tiny glass beads or bits of walnut shell. Each has its own advantages, and may affect the appearance of the finished product, as well as its cost.

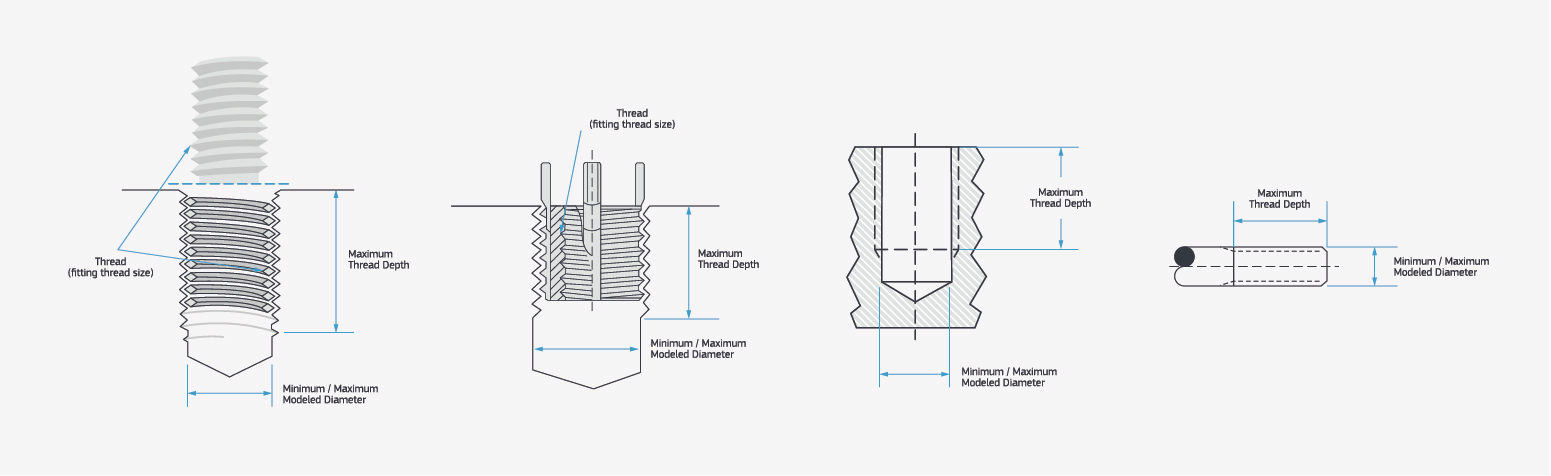

Designing for Accurate Threads

Adding threaded features to machined parts can also be a challenge. Internal threads can be created with a tap, a cutting tool that closely resembles the bolt or fastener that will at some point be screwed into the workpiece, or a special cutter known as a thread mill. Either way, deep threads are difficult for the same reason that deep holes are difficult, namely chip evacuation, and in the case of thread milling, radial cutting pressures. In most cases, a thread depth of twice the diameter provides plenty of strength, and costs less to produce. If this is insufficient, consider using inserts such as Heli-Coils or key inserts to bolster thread integrity, especially on plastic parts. Finally, thread tolerances are specified with an “H” limit, the most common being H2 or H3. The latter has a tighter tolerance, however, and is, therefore, a bit costlier to produce, so the best bet is to call out an H2 for all but critical applications.