It’s time to take a cold, hard look at an important question that’s bouncing around the Internet. Is your 3D printer going to kill you with toxic emissions?

Scientific journal Environmental Science and Technology just published the first comprehensive study of fume emissions caused by 3D printing. We sorted through the findings of the report so you don’t have to.

There have been a few studies on the health effects of 3D printing, but the results varied so much that it was hard to draw conclusions. With this recent paper, the French and U.S. scientists approached the topic systematically, testing five brands of printers and nine types of filaments.

Frankly, we’re kind of surprised this conversation is so late in coming — especially because so many of the exciting possibilities for 3D printing have to do with schools and hospitals. We’re hoping all those 3D printed hearts and sternums were printed safely so this ground-breaking work can continue!

To the Results!

The study is specifically concerned with the Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) category of 3D printing, where thermoplastic material in the form of filament spools are melted down and extruded through a nozzle to build up a model, layer upon layer. It does not cover Stereo-lithographic (SLA) 3D printing.

Two variables were tracked — ultrafine particles (UFPs) and hazardous volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

First, let’s talk about hazardous volatile compounds — these are airborne chemicals produced by the melting of filaments in order to feed them through the nozzle. The most surprising results of the study have to do with the two most popular filaments: PLA and ABS.

People usually refer to ABS by the acronym, so you might not know what it stands for: acrylonitrile butadiene styrene. Why is that important? Styrene is one of those hazardous volatile compounds — it’s toxic and maybe cancer-causing. While the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the United States doesn’t have protections against it, the Department of Heath and Human Services calls styrene “reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen.”

Fortunately, PLA (polylactic acid) breaks down into lactic acid — the same chemical that makes you sore after working out — so there’s no threat there.

Yeah… Toxic Emissions are Worse than We Thought

While styrene seems to be the main problem, other filaments give off other hazardous compounds: like caprolactam, which is offgasses from nylon and PCTPE, as well as exotic filaments like Laybrick and Laywood (they really tested everything).

Caprolactam is classified as non-carcinogenic, but the threshold for “acute exposure” is pretty low: 50 micrograms per cubic meter. The problem isn’t just the long-term health risks, it can also cause headaches, respiratory and eye problems.

The study shows that running a 3D printer for 45 minutes, assuming a standard 45 cubic meter office space ventilated at the standard rate, does raise hazardous volatile compound levels way above the averages tested by the EPA.

The caprolactam amounts 244 micrograms per cubic meter) far exceed the EPA’s suggested limit of 50. Styrene, to take another example, would saturate the space at 150 micrograms/cubic meter: infants show respiratory distress at 2 micrograms per cubic meter. In other words, don’t 3D print around your baby!

Lots of articles are reporting that the type of printer doesn’t matter, but it actually does seem to make a difference according to the study’s data. Printing with ABS filament on a MakerBot Replicator — even with the enclosure on — emits about 150 micrograms per minute, whereas the XYZ da Vinci gives off about 25.

Not that you need to run out and get a new printer. This is the first comprehensive study, and as they say, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. We’ll get to that next.

3, 6, 9, Damn You’re…Ultrafine. Particles

The second health risk the study measured is ultrafine particles. Obviously, it’s not great for your lungs to breathe in particulate matter. And 3D printers do give off these particles. But, when you break it down, the emissions aren’t any more than driving in a car or using a hairdryer.

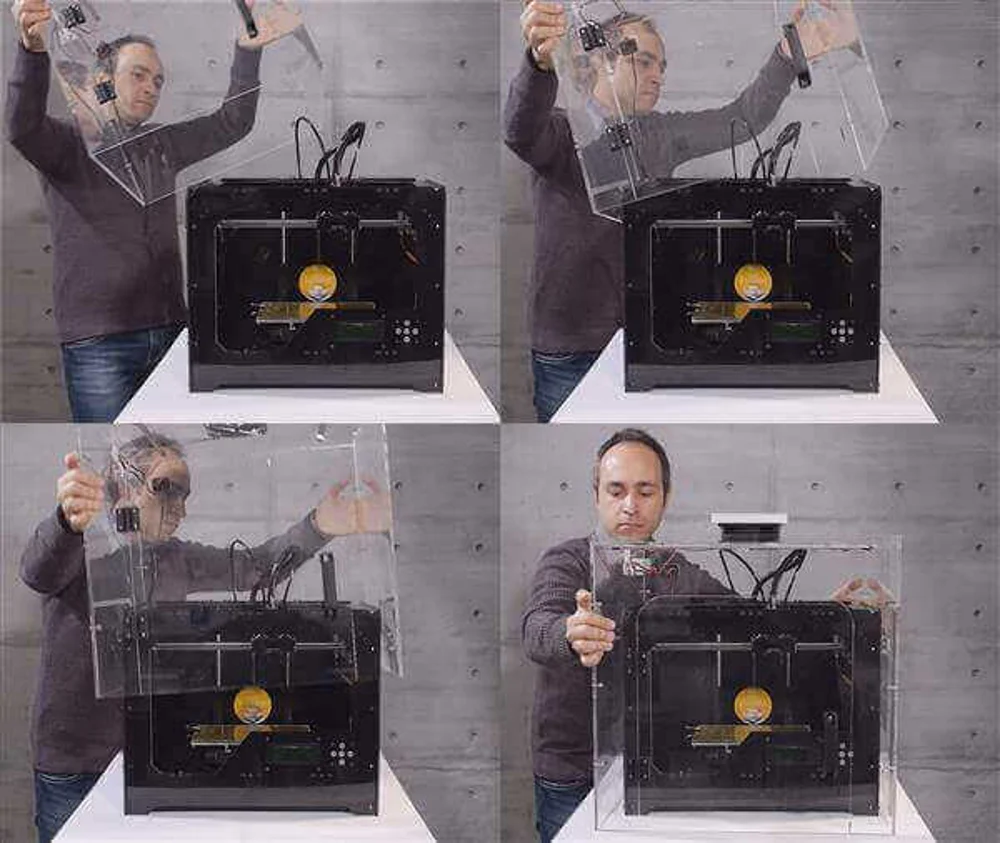

But still, let’s be smart about this. One of the tests the scientists ran was to print off a MakerBot with the enclosure attached and intentionally removed — it didn’t make a huge difference (a 35 percent reduction) but it’s worth paying attention to the operating instructions to be as safe as possible.

Here, too, ABS is an exponentially more dangerous choice (with UFPs around 1011 rather than 108)

So Where Does This Leave Us?

Ventilation, ventilation, ventilation. If you’re printing with ABS, use a filtration system of some kind. There are plenty of DIY options and more commercial ones in the development pipeline.

Bottom line: be sure to ventilate your space — the experimental models the researchers used assumed standard office ventilation, which is clearly not adequate to maintain healthy, average air-levels. In their words:

“Until then, we continue to suggest that caution should be used when operating many printer and filament combinations in enclosed or poorly ventilated spaces or without the aid of gas and particle filtration systems. This is particularly true for both styrene- and nylon-based filaments, based on data from the relatively large sample of printers and filament combinations evaluated here.”

The research team is even working on a modeling software so that end-users can easily predict VOC and UFP levels based on the machine, filament, and volume of their print so that both users and researchers can come up with ways to reduce exposure, like better HVAC systems, spot ventilation, or building newer, better enclosures. The research team also has some suggestions for manufacturers, too:

“Manufacturers should work toward designing low-emitting filament materials and/or printing technologies. Third, in the absence of new low-emitting filaments, manufacturers should work to evaluate the effectiveness of sealed enclosures on both UFP and VOC emissions or to introduce combined gas and particle filtration systems.”

And some makers have already taken up this charge, working to share information about less hazardous filaments. Clean Strands, for example, offers a virtual marketplace for algae, starch, and wood-based filaments. They sat down to talk with one of the lead researchers on the study about how to move forward. Dr. Brent Stephens comments,

“I would hope that we can stop researching 3D printer emissions and get on with using them safely in all kinds of environments. My sincere hope is that if any community can figure out how to reduce or control emissions from these devices, it is the vast, vibrant maker community!”

Amen, Dr. Stephens. We’ll print to that!